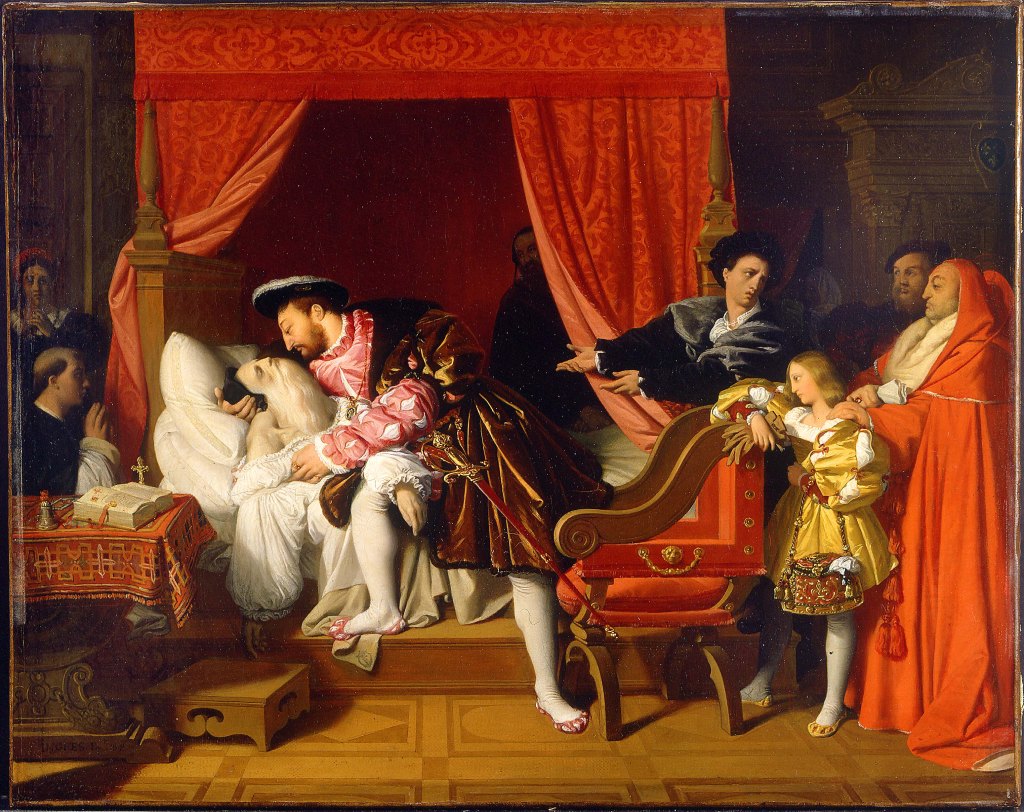

Catherine de’ Medici takes the reins under the novel title of Governess of France. Just as she assumes power, a crisis that will overshadow the rest of her life begins to take shape.

Transcript

Because it’s been a while, let me remind you of where we are in our story. King Francois II, son of Catherine de’ Medici and King Henri II of France, has died from an agonizing illness. Catherine’s next oldest son Charles-Maximilien had to come to the throne, regardless of his age. The king is dead, long live the king, as the old French saying goes. Only ten years old, Charles-Maximilien was crowned as King Charles IX. However, the real ruler of France was no one other than Catherine. The three men most likely to successfully challenge her claim as the queen regent, the Duc and Cardinal de Guise and Antoine de Bourbon, had all been neutralized. The Guise brothers agreed not to stake a claim on the regency in exchange for King Francois taking the blame off their shoulders for certain illegalities at the trial of Antoine’s troublesome brother, Louis, the Prince de Condé. As for Antoine, the fact his brother was convicted of being involved in a conspiracy to kidnap King Francois made him vulnerable enough for Catherine to bring him to heel. But Catherine was smart enough to use the carrot along with the stick. She had Condé freed from prison and granted Antoine the important post of Lieutenant General of France. For the Guises, she confirmed the Duke of Guise’s position as a general of the French army. The year before Charles IX’s ascension, Catherine had also married her daughter Claude to the Guises’ cousin, Duke Charles III of Lorraine.