Far from a fairly tale life, to secure her future Catherine de’ Medici must overcome snobbery at the royal court, anti-Italian racism, escalating religious and political tensions, her husband’s bizarre love for his own surrogate mother Diane de Poitiers, and even her own body’s seeming inability to get pregnant with an heir to the French throne.

Support the podcast on Patreon or by making a one-time donation below.

Make a one-time donation

Make a monthly donation

Make a yearly donation

Choose an amount

Or enter a custom amount

Your contribution is appreciated.

Your contribution is appreciated.

Your contribution is appreciated.

DonateDonate monthlyDonate yearlyTranscript

We don’t really have a clear picture of what life was like for Catherine in the French court. She did have more than a dollop of French aristocratic blood through her mother, but she was still seen as a daughter of the bourgeoisie, in a royal court where even a marriage between a prince or princess and a member of the nobility might be considered a misalliance. I think sadly most of us can have at least have a vague idea of the snobbery and cliquishness she faced on a daily basis.

If this experience of being a daughter of a family still known as bankers and merchants in Europe’s most exclusive royal court wasn’t bad enough, the political winds would turn against her. Less than a year into her marriage to Prince Henri of France, Catherine’s benefactor Pope Clement VII was dead. His successor, Paul III, had no reason or obligation whatsoever to fulfill any agreements Clement had made with France. Nor was Catherine showing any signs of being pregnant. There were strictly only two reasons for a royal marriage: to put the seal on a political alliance and/or to have an heir. Catherine was fulfilling neither duty. No wonder King Francois remarked on Catherine, “The girl has come to me completely naked.”

Speaking of Francois, he has played almost as important a role in our story as Charles V, but we haven’t really met him. This is a good point to change that. King Francois I was born on September 12, 1494. I mentioned his mother Louise of Savoy, who along with his sister Marguerite of Navarre were the biggest influences in his life. This was because his father, Charles, Count of Angouleme, died when he was only two years old. While he was still a child, he became the heir presumptive to the crown of France after his cousin King Louis XII became king. The Salic Law prevented either of Louis XII’s two daughters from becoming queen, and Francois was the next patrilineal male in line, being directly descended from a brother of King Charles VI. Louise of Savoy fiercely resisted any attempts by Louis XII to dominate her son’s upbringing and education, although Louis XII did at least manage to have Francois live at court starting at an early age. He also arranged for Francois to marry his eldest daughter, Claude. Since she was the heiress to the once independent duchy of Brittany, the marriage was strictly for keeping the duchy in the French orbit. By New Year’s Day of 1515, Louis XII died without a son, despite his desperate attempt to father a son with his young, attractive bride Mary Tudor. Queen Claude would die nine years later, but not before mothering seven children, including Catherine de’ Medici’s groom, Henri.

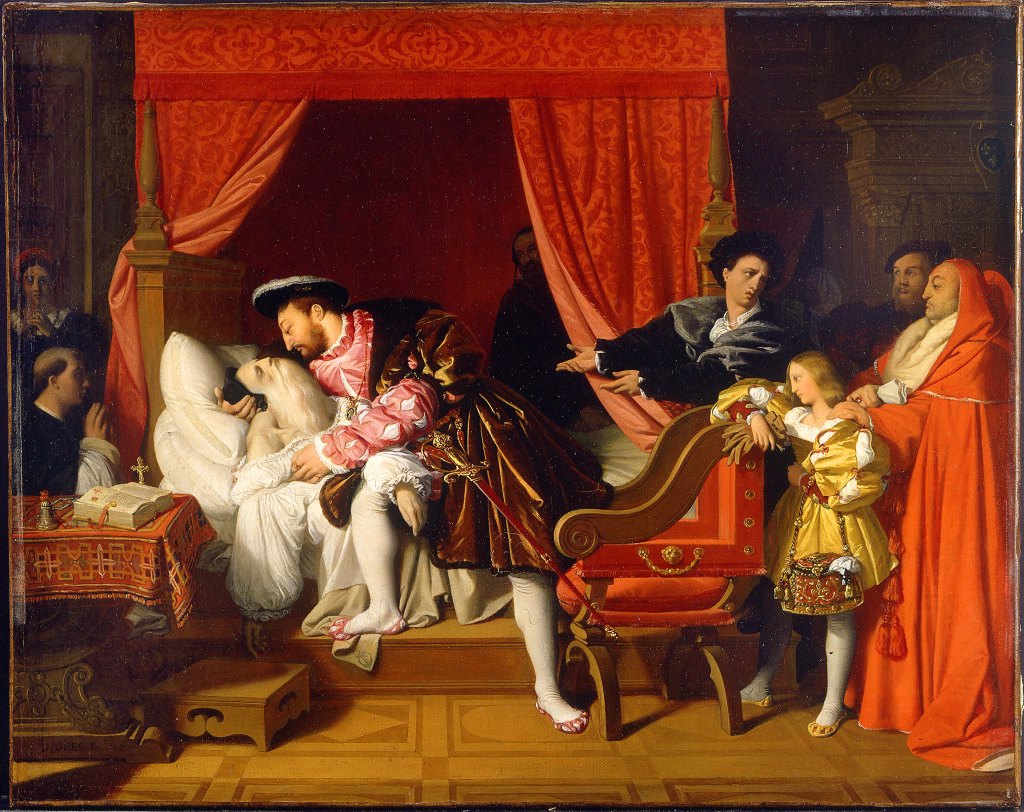

Francois became in many ways the ideal Renaissance king. He was well-read and a great lover of art, especially Italian art, something that his beloved mother Louise of Savoy inspired in him. He patroned such Italian luminaries as Leonardo da Vinci, who according to legend died as the king himself cradled Leonardo’s head in his arms as he died; the goldsmith Benvenuto Cellini; and the artist Giovanni-Battista Rosso, among others. Francois was also said to have had a sizable collection of erotic art, although of course this detail tends to get left out of the textbooks. He was also a talented speaker, having the invaluable skill of pontificating even on topics he was not at all knowledgeable about. Still, there are suggestions in the records here and there that he was shy around strangers. An English ambassador, Thomas Cheyney, remarked, “If a man speak not to him first, he will not likely begin to speak to him, but when he is once entered, he is as good a man to speak to as ever I saw.”

He was also handsome, despite having such a massive nose one of his epithets was Francois of the Big Nose, and extremely athletic. Francois was a fanatical hunter and an avid tennis player and jouster, even though he was plagued with ulcers throughout his life. During the Field of the Cloth of Gold, a conference where Francois and King Henry VIII met in person at the border France shared with the English-held territory of Calais, Francois and Henry wrestled. Even though Henry was at the time at the peak of his own muscular prowess, Francois pinned him, much to Henry’s chagrin. Francois even matched his strength with personal courage. At a time when the new rules of artillery warfare meant kings were becoming more likely to be behind-the-scenes tacticians or stay far from the frontlines entirely than actually leading their nobles into battle, Francois actually did put his neck on the line, joining the fray. Even during one hunting party, it took Francois’ mother and sister to talk him down from running off to kill a trapped and enraged boar. Of course, that’s why Francois was captured at the Battle of Pavia in the first place. Francois’ foreign policy was also audacious and reckless, as we’ve seen. He broke treaties, gave up two of his sons as hostages, and, most shocking of all to Europe, signed a military alliance between France and the Ottoman Empire against Charles V. It was this move that forced Charles V to make overtures to the Ottomans’ only major Islamic rivals, the Safavids of Persia, something that must have galled the devout emperor.

Francois was also a notorious womanizer. Some of these stories became exaggerated by later Protestant writers hostile to him, like the allegation he committed incest with his own sister, but what made such propaganda potent was that there was a ring of truth. There’s a plausible theory that he may have caught syphilis at some point in his life. Mary Tudor, queen of Louis XII, complained that Francois was “importunate with her in diverse matters not to her honour.” Still, Francois’ life was defined by powerful women like his mother and sister, and he seems to have genuinely enjoyed the company of women not just as sexual conquests. He even had a little group of female courtiers, called La Petite Bande, who conversed with him and joined him on his hunting trips. Like other French kings from the past, he had a maitresse en titre, meaning roughly “official mistress” who openly appeared with him in public. By Catherine’s time, this woman was Anne d’Etampes, a noblewoman from Picardy in northern France. An English diplomat was scandalized when Francois married a second time to Charles V’s sister, Eleanor, and Francois appeared during the wedding festivities with Anne right by his side. One snide remark about Francois was, “Alexander the Great attended to women when there was no more business to attend to. His Majesty attends to business when there are no more women to attend to.”

By the time Catherine joined it, Francois’ court was a tense place to be. Besides the petty jealousies between rivals that are always a fact of life in the centers of power, Francois’ court was basically split between two factions. On one side was what might be called the pro-imperialist faction, who wanted Francois to make a permanent peace with Charles V and form a united front against the Ottomans and, more importantly, the growing horde of Protestant heretics. Their ranks included Anne d’Etamps and Francois’ youngest and favorite son, Charles. On the other side of the chessboard were the anti-imperialists, which was led by the king’s friend, the talented general Anne de Montmorency [Mon-more-ensi]. The factional politics at the French court were complicated and encompassed a variety of personalities and agendas. But for our purposes we can say that the political divisions at Francois’ court also overlapped with religious divisions, the same which would grow and consume Catherine de’ Medici’s own life and reign.

I’ll be upfront with you. The French Wars of Religion, which are looming just on the horizon like a thunderstorm before the relatively sunny day that is King Francois’ reign, is an incredibly complicated topic. In fact, I’d go so far as to say it’s one of the most complex conflicts in all of history. It wasn’t just about Catholics versus Protestants, it intersected with and fed into ongoing struggles between royal power and the nobility, between different regions of France, between the city and the countryside, between classes, and between individuals and families. In fact, it wasn’t even a straightforward confrontation between Protestants and Catholics. It was more like a three-way clash. There were the traditionalist Catholics, who also happened to be the most likely to be pro-imperial, because they wanted all of Catholic Europe to unite against the Protestant threat. Many if not the vast majority weren’t against the idea of church reform, but any such reform had to come down from the top, either from the Pope or an official ecclesiastical council. There were the Protestants. France even got its own species of Protestants, the Calvinists, a movement founded by a lawyer named Jean Calvin that had much in common with the Lutherans yet was also distinct. These people increasingly came to be called Huguenots in French. Historians aren’t exactly sure where the term came from, but it might have come from a regional term in French for spirits who wandered the earth at night, because to avoid persecution Calvinists had to meet secretly at night. Finally, there were the reformist Catholics, like Marguerite of Navarre, who followed the lead of humanists like Erasmus in the Netherlands. They were willing to accept efforts to reform the church outside the official hierarchy, like from the bottom-up or by secular governments, especially reforms that would target corrupt members of the clergy and superstitions like obviously false relics and reports of miracles and allow lay people a greater personal understanding of the Bible. The line between reformist Catholic and Protestant could be blurry, even after Luther and Erasmus had their dramatic falling out, blurry enough that even being a reformist Catholic could be dangerous depending on the time and place. This wasn’t always the case, but the Protestants and reformist Catholics tended to also be anti-imperial, more so as Charles V escalated his campaign against Protestantism.

French Protestantism, especially Calvinism, was especially popular in the South. Southern France had always had a fraught relationship with the north. Even as early as the centuries immediately following the fall of the Western Roman Empire, the South was considerably different. It was richer and more urbanized than the north, it had its own language Occitan [Aksutan] or Provencal and its own cultural traditions, and it had a tradition of having its own kings and virtually independent dukes. Indeed, there are several flashpoints in history where southern France might very well have gone the way to form its own nation-state, most recently when Charles de Bourbon rebelled against King Francois and signed an agreement that Henry VIII of England would get northern France while Charles would become king of a new kingdom carved out of southern France. Also memories in the region still carried impressions of the thirteenth century, when the French monarchy in an alliance with the Pope carried out a genocidal campaign against the locals, all for the cause of rooting out the heretical Cathars, and at the same time snuffed out much of what was left of southern autonomy. Some historians would agree that it wasn’t a coincidence, even centuries later, that Protestantism proved so popular in the south.

At first, Francois was more or less tolerant of Protestantism, despite the occasional burning of an accused heretic. If anything, Francois looked at Protestantism as a potent weapon against Charles V. That attitude changed when the threat suddenly came close to home, quite literally. While staying at his riverside chateau in Amboise, Francois woke to find someone had on the morning of October 19, 1534 committed an unthinkable breach of security by placing a placard against his door. The placard denounced the Catholic mass, especially the Catholic belief that the body and blood of Christ was manifested in the ritual of the Eucharist. Francois soon learned that similar placards had been placed around five of France’s largest cities, including Paris. No doubt the person who put the placard on the king’s door had hoped that Francois would become sympathetic to such criticisms. After all, Francois had his own problems with the Pope and the Church, even toying around with the idea of making the Church in France independent from the Church in Rome and under the monarchy’s stewardship. Independence was one thing; challenging the most basic and sacred beliefs in the faith was another. The Parliament of Paris with Francois’ approval had numerous Protestants burned for heresy. One unlucky merchant was hanged just because he was Dutch, so the mob assumed he was a German and thus a Protestant.

So….in such an atmosphere of conflict and change, how did Catherine sail through the storms? Well, rather brilliantly. While the sources haven’t left a month-by-month breakdown, it’s clear that Catherine was a master at making the right friends. She befriended both Anne d’Etampes, Marguerite de Navarre, and her brothers-in-law, all the while managing not to throw her lot in with either the anti-imperialist or pro-imperialist camps. She even managed to become part of the king’s inner circle. As much as Catherine’s marriage ended up being a bum deal, Francois seems to have genuinely liked her. Maybe it was just some chivalric instinct, but I like to think he had an empathy toward intelligent women like his mother and sister that Catherine consciously or not played on. Even so, Catherine worked toward winning over her father-in-law. She worked her way into La Petite Bande, joining Francois on the hunt and laughing at his dirty jokes. Unlike Catherine’s modern biographer Leonie Frieda, I think Catherine who showed signs of having a wicked sense of humor and was known to read literature that might be considered risqué at the time probably did appreciate the king’s sense of humor. While she always spoke French with a thick Italian accent and had to write French phonetically, she was clearly able to keep up with Francois and his circle of intellectuals. She shared Francois’ interests in art and literature, after all, and could offer in any conversation her own personal interest in astronomy and physics.

The one person Catherine failed to win over was her own husband. Whatever traumas they had in common, Henri did not feel the same way about Catherine that she felt about him. His heart belonged to another: Diane de Poitiers, even though she was 19 years older than Henri. When he returned from being a hostage in Spain, she became his mother figure, since Henri’s own mother had died when he was only five years old. A daughter of the French aristocracy herself, she had been married to an elderly nobleman, Louis de Breze, who was forty years her elder and was acclaimed as one of the ugliest men in France. Still, he was her ticket to becoming a fixture at the French royal court. A tall, elegant woman, Diane dressed herself only in black and white, ostensibly as a gesture of mourning for her husband but also a way to promote her identification with her namesake, the Roman moon goddess, Diana. So Diane also assumed the crescent moon as her personal emblem. Never marrying again and living off her inheritance from her husband, Diane became something like a prototype of a modern celebrity, with visitors to the court wishing to see her for the sake of seeing her. Indeed unlike other court ladies Diane never wore makeup and instead washed herself with cold rainwater. Her rigorous hygiene regiment was so famous that a book on the subject of hygiene was dedicated to her. Still, Diane was apparently just Henri’s confidant and surrogate mother…for the time being.

Things were difficult enough for Catherine but then an unexpected tragedy shook the already flimsy foundations of her marriage. On August 10, 1536, the heir to the throne, the Dauphin Francois, played an intense game of tennis with his secretary Sebastiano de Montecuculli, who had been one of the Italian servants who accompanied Cathreine to France. As soon as the game was over, the Dauphin asked for a glass of ice water, overcome by either exhaustion or even heatstroke. Upon drinking the water, the Dauphin collapsed and soon died. Given the circumstances, people immediately suspected the water had been poisoned. The fact that Sebastiano de Montecuculli had been present suggested a culprit. The accusations were sharpened by widespread anti-Italian bigotry. As fashionable as Italian art and humanism was in France, Italians were derided for being crafty poisoners. Nor did it help that under the italianophile King Francois many Italians had taken jobs and positions at court away from hardworking Frenchmen or so they thought. Either way, poor Sebastiano, who also happened to have worked for Charles V before he came to France, was doomed. Accused of killing the Dauphin at the behest of Charles V, Sebastiano was found guilty and executed at Lyons. He was given the traditional execution of an assassin of someone with royal blood: his legs and arms tied to horses, who were then forced to run, ripping him apart. Catherine was much, much luckier than poor Sebastiano, of course, but she did not go away unscathed. She too was Italian, after all, so why wouldn’t she conspire with a fellow countryman who had been with her since she came to France in order to make herself the future queen? The suspicions deepened when Charles V’s ambassadors, desperate to counter the accusations, instead suggested that Catherine was the mastermind of any poisoning plot. On top of that, becoming the wife of the heir to the throne made Catherine’s lack of a son even more of a liability.

A year later, something happened that seemed to prove that the couple’s infertility was on Catherine. The wars between France and the Holy Roman Empire had flared up again. Henri begged his father to let him prove himself on the battlefield. Francois had always been a distant and critical father to his sons Francois and Henri, possibly because the two boys had become too quiet and reserved for Francois’ liking when they returned to Spain as a result of the PTSD that Francois caused by handing them over as hostages. Instead, Francois saved most of his affection for his youngest son, Charles. But perhaps realizing that the heir to the throne could use some warrior credentials, Francois let Henri lead an effort to repel an imperial invasion in Provence and the Piedmont region. I say “lead”, but really it was in name only, while Anne de Montmorency did the heavy lifting. Still, Henri and de Montmorency became close friends, so close that he would in the years to come turn a blind eye to his apparent heretical leanings.

At some point during the campaign, Henri had sex with the sister of a servant from Savoy, Philippa Duc. The woman became pregnant and gave birth to a daughter whom Henri named after his best friend, Diane. When Pope Paul III was able to broker a peace between the Holy Roman Empire and France, Henri returned to the French court with his newborn daughter in tow. This was a massive blow to Catherine. Now it seemed Henri could produce children. This gave fuel to the arguments that Henri should annul his marriage to Catherine and marry again.

Even after all this, Catherine had another humiliation in store. It was probably shortly after Henri’s return that he and Diane slept together for the first time. Why is something of a mystery. What we can say is that a woman who was a mother figure to a much younger man suddenly becoming his lover is something that would get one cancelled today. Even at the time, it would have been considered a bizarre, if not outright scandalous, pairing. The evidence Diane became Henri’s mistress at this time is circumstantial, but compelling. Henri started dressing in white and black, just like Diane, and adopted the crescent moon as his own emblem. Monograms combining their initials, H and D, also started to appear, although one version also had a couple of Cs for Catherine within the H. It was unlikely that Diane would conceive a child, since she was already in her late 30s, and there was no question that she and Henri could ever marry without sparking a massive scandal. In fact, compared to his father’s open affairs, Henri tried to keep his relationship with Diane secret, or as secret as they could even with him adopting her emblems and clothing. Catherine, of course, knew. In a letter written to her daughter Elizabeth many years later, in a stunningly candid moment, wrote:

“If I was polite to Diane, it was for his sake, yet I always told him it was against my will; for no wife who loves her husband ever likes his whore. Such a woman deserves no other name, though it is an ugly word for us to use.”

However, the two women did strike up an unlikely alliance. Catherine preferred Diane over a woman who could provide Henri with even more illegitimate children, whose mere existence would diminish Catherine’s own standing. And Diane had every reason not to see Henri get rid of Catherine and replace her with a younger, more beautiful queen. At last, one day, Catherine decided to break the tension and stake everything on one hand. One day, she met with the king and fell to her knees before him, sobbing. She pleaded with him that if he wanted to see Henri married to a woman that could provide him with heirs, then she would agree to an annulment without a fight. She only wanted Francois to allow her to stay in France, rather than send her packing back to the land where she was only a powerless orphan. Moved, Francois lifted Catherine up and comforted her, saying, ““My child, it is God’s will that you should be my daughter and the wife of the Dauphin. So be it.” It was a triumph, not unlike when her ancestor Lorenzo the Magnificent threw himself at the mercy of the King of Naples. Still, Catherine had only won for herself time. The longer she had no heir, the weaker her position would be.

Catherine resorted to drastic measures, which are even more drastic in modern eyes. There were countless folk remedies for infertility, and Catherine seemingly tried them all. She wore magic charms, drank the urine of pregnant animals, consumed powders made from the genitals of deer, boars, and cats, and a concoction of a horse’s milk, a sheep’s urine, and a rabbit’s blood. She even drank unicorn’s horn in water, which was probably a rhino’s horn. Nothing seemed to work, at least not until she consulted with the pioneering French doctor Jean Fernel.

I should probably mention here that we are about to get into some rather delicate details about the intimate lives of people who have been dead for longer than the United States of America has existed. If you’re not into that kind of thing, skip ahead to the last few minutes of the episode.

Now that it’s just us, let’s continue. Historians have speculated on how Catherine suddenly became fertile after 13 years of marriage. Perhaps she had inherited a mild case of congenital syphilis that made it difficult to conceive, or one of the folk treatments actually inadvertently worked by altering her ph balance. However, a paper titled “The infertility of Catherine de Medici and its influence on 16th century France” written by three urologists seemingly solved the mystery. Taking together present-day medical knowledge and pieces of evidence from sources at the time, they argue that Fernel’s diagnosis was correct. According to Fernel, it wasn’t Catherine, but Henri after all. He had some kind of deformity in his genitals that made conception more difficult, so he suggested that she and Henri try different positions. This goes along with another account that Diane de Poitiers actually forced Henri to go to bed with Catherine every night and suggested that the two make love “a levrette”, which means “like a female greyhound.” These are the things that can actually change the course of history, I’m sorry! I will admit, there is something particularly uncomfortable discussing the intimate lives of a couple that died centuries ago.

But yes, Catherine would go on to have ten children, of whom seven would live to adulthood. Her first son was born on January 19, 1544. He was named Francois, after his grandfather who made sure he was present for the birth. Also present was Diane de Poitiers, who assisted Catherine giving birth. So began the strange, three-way marriage between Catherine, Diane, and the future King Henri II.

Thank you for listening, and buona note.