Catherine de’ Medici takes the reins under the novel title of Governess of France. Just as she assumes power, a crisis that will overshadow the rest of her life begins to take shape.

Transcript

Because it’s been a while, let me remind you of where we are in our story. King Francois II, son of Catherine de’ Medici and King Henri II of France, has died from an agonizing illness. Catherine’s next oldest son Charles-Maximilien had to come to the throne, regardless of his age. The king is dead, long live the king, as the old French saying goes. Only ten years old, Charles-Maximilien was crowned as King Charles IX. However, the real ruler of France was no one other than Catherine. The three men most likely to successfully challenge her claim as the queen regent, the Duc and Cardinal de Guise and Antoine de Bourbon, had all been neutralized. The Guise brothers agreed not to stake a claim on the regency in exchange for King Francois taking the blame off their shoulders for certain illegalities at the trial of Antoine’s troublesome brother, Louis, the Prince de Condé. As for Antoine, the fact his brother was convicted of being involved in a conspiracy to kidnap King Francois made him vulnerable enough for Catherine to bring him to heel. But Catherine was smart enough to use the carrot along with the stick. She had Condé freed from prison and granted Antoine the important post of Lieutenant General of France. For the Guises, she confirmed the Duke of Guise’s position as a general of the French army. The year before Charles IX’s ascension, Catherine had also married her daughter Claude to the Guises’ cousin, Duke Charles III of Lorraine.

It was a good start to the reign. Catherine had proven her skills as a chess master and had shown that she would not let her own personal vendettas and grievances get in the way of good politics. She was also aware of the importance of public relations in cementing her new position. Instead of using the title of queen regent, Catherine had a royal seal specifically designed for her as “Governess of France.” The artist who designed it depicted Catherine wearing a crown along with a widow’s veil and holding a scepter while with her other hand she pointed her index finger up, a traditional gesture of command. Under the image were the words, “Catherine by the grace of God, Queen of France, Mother of the King.” However, during the coronation ceremony when Charles IX was crowned king of France, the boy started sobbing when the heavy crown was placed on his head. If Catherine interpreted this as an omen, there is no sign.

I should take a moment here and go into a little detail of what exactly Catherine had gotten herself into and what it meant to be the ruler of France at the time. It is true that for centuries the monarchy had been gradually asserting its power over the nobility. As a result, the days when a great magnate had all but absolute control over their own territories, coined their own currency, and was able to raise an army that could threaten the monarchy itself were long gone. Nonetheless, France was still a very decentralized country, even by the standards of the time. There was no national representative assembly that had regular meetings which by this point had developed in many western and central European countries, like the Parliament of England, the Cortes of Castile, the Imperial Diet of the Holy Roman Empire, or the General Sejm (SAME) of Poland, among others. The closest thing to such a body was the Estates General, so named because it involved representatives of the three traditional classes or estates of France – the clergy, the nobility, and the “Third Estate”, commoners. It met fairly regularly during the Hundred Years War, when the kings happened to need their subjects to agree to give them a lot of money, but by Catherine’s time it hadn’t even been called once since 1484.

The assemblies that did meet regularly were the different parliaments representing different regions around France. Despite what the name implies for English speakers, the parliaments didn’t pass or amend laws. Instead they were more like courts. We’ve seen they had the power to order arrests in their jurisdictions and their decisions could set lasting legal precedents. The Parliament of Paris did have more power and prestige and became something like the Supreme Court of the United States, the court of last resort that would take on high-profile cases. But all the Parliaments did have one check on the legislative power of the monarchy. While the monarchy could pass laws in the form of edicts that affected the entire kingdom, any parliament had the right to refuse to officially register the edict or have it enforced. In such a case, the parliament had to write up and submit an explanation of their objection to the law. Afterward, the king could override the parliament’s refusal through writing an official letter rebutting the parliament’s objections and asserting the king’s authority. More effective and dramatic was the act of the lit de justice, literally “bed of justice.” The name referred to the fact the king would appear before parliament on a throne covered by a canopy with the colors of state, resembling the coverings over the bed of an upper-class person. This forced the parliament to register the edict, but the key was that the king himself had to appear in the parliament’s chambers in person. The king could also force his will by simply having members of parliament imprisoned since the king of France notoriously had the power to have any subject imprisoned without trial or by revoking the parliament’s traditional rights. However, this was even for the king a very risky move that could provoke outrage, and one that kings usually avoided up to that point.

As you might expect, the various parliaments were mostly filled with nobles and wealthy bourgeoisie. It was these local elites and their patronage networks who also dominated regional magistrate and church offices with little practical oversight from a higher authority. Also, France was a confusing patchwork of local privileges, taxes, and legal traditions. One town might enjoy a specific tax exemption that the next town over did not, while an entire region could have a special trade privilege. Northern France even had a very different legal system, one where judges and their interpretations of custom had a lot of leeway, than that of most of southern France, which instead depended on written law. There would be attempts to streamline this unwieldly system. Catherine de’ Medici herself would get the Estates General to finally standardize the system of weights and measures across France, and the future King Louis XIV would create a system of government-appointed representatives to oversee regional administration. But overall the confusing and chaotic state of French administration would remain the status quo until the French Revolution would finally sweep away the ancient regime. One might describe Catherine’s job as Governess of France as herding cats.

Right away, Catherine had to deal with the pretensions of the Guises and the Bourbons. There was a proposal to wed her newly widowed daughter-in-law Mary Queen of Scots to the new king. Such a union would have been considered incestuous in the eyes of the Catholic Church – indeed, it was the same type of marriage that led to Henry VIII of England breaking away from papal authority – but a papal dispensation could be arranged. However, Catherine quickly squashed the idea, to keep the Guises from regaining their foothold in the royal family. Antoine de Bourbon also got enough courage to bring up in a meeting of the privy council that he should fill in for Catherine if she ever became ill. Catherine decisively responded, “‘My brother, all that I can say is that I shall never be too ill to supervise whatever affects the service of the King my son. I shall ask you therefore to withdraw your request. The case you foresee shall never arise.’ “

Aside from the unending Bourbon and Guise feud, Catherine was faced with two challenges. The first was the shoddy state of France’s economy, which had never recovered from the Italian Wars and, unknown to anyone at the time, was still being impacted by the Europe-wide inflation brought on by the looting of gold and silver from the Americas. The second was the religious tensions, which still threatened to boil over. Catherine’s first act was to cut corners at the royal court, reportedly bringing down the court’s budget by over a million livres. Next, she called the long promised meeting of the Estates General. She had to call the Estates General twice, because negotiations during the first meeting fell apart. At the second meeting, Catherine scored some victories. She was able to reduce military spending, get the estates to agree to some tax raises and forced loans, and secure some income from lands that had been previously handed over to the church. Catherine was far less able to handle the religious issues. All she could accomplish was securing some support for a conference with religious representatives. The conference was finally held months later in September of 1561 and was named the Colloquy of Poissy for the convent near Paris it was hosted in. A moderate Huguenot, Theodore de Bézé, led the Protestant delegation. When it was De Bèze’s turn to speak, his speech actually affected the audience until he denied that anything supernatural happened in the rite of the Eucharist. Then the mood of the audience turned hostile. A cardinal turned to Catherine who was overlooking the proceedings with the king and her youngest son Edouard-Alexandre and demanded to know, “How can you tolerate such horrors and blasphemy to be spoken before your children who are still of such a tender age?” Perhaps taken aback, Catherine merely replied that she and her sons would always be good Catholics. Any chance the proceedings would lead to anything productive died then and there. After over a month of tensions and heated arguments, the Colloquy resulted in nothing. Still, Catherine was committed on the course of religious toleration.

This raises the question. What were Catherine’s views on religion? I think her modern biographer Robert Knecht has it right: “Catherine, it seems could not understand religious fanaticism. Having been born and brought up as a Catholic, she practiced her faith out of habit and also because the liturgy was to her taste. But religion did not enter her soul. When she tried to justify her actions or, later in life, advised her daughter Marguerite on her conduct, she drew her precepts from human wisdom, never from religious dogma.” In a letter to her daughter Elizabeth, who was now Philip II’s wife, Catherine protested, “Do not let your husband the King believe an untruth. I do not mean to change my life or my religion or anything. I am what I am in order to preserve your brothers and their kingdom.”

What Catherine expresses here is the genuine rumor circulating around the papal court and Spain that Catherine’s children, and possibly the queen herself, were being seduced by the Protestant heresy. In fact, there seems to have been a kernel of truth that at first Catherine didn’t try to keep her children from having Huguenot friends and reading Huguenot materials. The allegations were given more fuel from reports like how the nine-year-old Edouard-Alexandre was said to refuse to go to Mass and once snatched a Catholic prayer book away from his sister Margot. Then there was an almost sitcom-like incident that happened while Catherine was meeting with the papal ambassador. King Charles, Antoine de Bourbon and `1q2 of Navarre’s son Henri, and a group of their friends barged into the room dressed up as cardinals and bishops with the king riding a donkey. Catherine just burst out laughing. The papal ambassador, however, was not so amused, nor was the Pope who received a detailed account of the incident.

This is mostly speculation on my part, but I think Catherine’s attitudes were not just because of her political sensibilities, although they certainly played a part. She was being a Medici. True, the Protestant Reformation never really reached Florence. But she would have heard first-hand accounts of scholars being terrorized and works of scholarship and art being destroyed under Savonarola. It was religious fanatics who caused civil unrest in Florence and gave not just her family, but her personally, so much grief over the years. Also she had the example of her famous ancestor Lorenzo de’ Medici and Popes Leo X and Clement VII, all of whom were of course devoted to the Catholic faith but were still moderate in their dealings with controversial humanist scholars and Jewish communities. Indeed, she might have just seen letting her children read books by Protestants as a natural and useful part of their education. Nonetheless, Catherine was smart enough to recognize a public relations disaster, and she cracked down on her children’s access to Protestant materials.

But it was not enough, and it probably never would have been enough. As queen regent Catherine was in front of the throne rather than behind it. However, the price for this promotion was that she could no longer shield herself from any backlash to her policies. Her old enemy Montmorency, who was still a devout Catholic even though all of his nephews had converted to Protestantism, and the Guise brothers formed an alliance that was ominously named the Triumvirate after the alliance between Julius Caesar, Crassus, and Pompey the Great. On the basis that Catherine was letting France get rolled over by the Protestant menace, the Triumvirate schemed with King Philip of Spain to have Catherine deposed and put the Guise brothers in power. Well aware of this, Catherine tried to get in King Philip’s good graces and keep the Triumvirate from cementing their ties to Spain. The Guises tried to get Mary Queen of Scots betrothed to Philip’s son and heir Don Carlos, who was the son of Philip’s first wife, Maria Manuela of Portugal. Catherine countered by instead proposing that Don Carlos marry her daughter Margot. In the end, both overtures bottomed out, which is just as well for Mary and Margot because if Don Carlos was alive today he would have been singled out as a future serial killer or school shooter. He tortured horses and rabbits, sadistically abused women, and would end his days under house arrest for threatening to kill his father, dying as a result of his own hunger strikes.

In the meantime, Catherine continued to be pestered by the Triumvirate. She did not dare move against them, even though they talked openly of how she was unfit to rule as regent and negotiated with the King of Spain. Of course, if anything, the Triumvirate’s heavy-handedness and outright treasonous tantrums only backfired. The Huguenots might have been misguided or even outright heretics in Catherine’s eyes, and some of their printed materials had maligned her, but in person the Huguenots always treated Catherine with respect and deferment. On the other hand, the Triumvirate was involved in a half-hearted attempt to abduct Edouard-Alexandre, presumably to separate him from any Huguenot influences. By January of 1562, Catherine thumbed her nose at the Triumvirate by issuing the Edict of St. Germain, which was meant to provide a general settlement for the Huguenots until the papacy completed its deliberations at the Council of Trent on church reform and how to deal with the Protestants. It allowed Protestants to worship, but only in rural areas, and they could not assemble after sunset or arm themselves. At the same time, nobles were still given the right to use arms to defend the Protestants on their estates from harassment. It was a very limited extension of tolerance, but at least it was a grudging recognition of their right to exist. Philip II expressed his horror in a letter written directly to Catherine. She replied, “For twenty or thirty years now we have tried … to tear out this infection by the roots, and we have learned that violence only serves to increase and multiply it, since by the harsh penalties which have been constantly enforced in this kingdom, an infinite number of poor people have been confirmed in this belief … for it has been proved that this fortifies them.” Whether or not Catherine really saw Protestantism as an infection that needed to be eradicated is a matter for debate. On my part, I see her actions as suggesting that she gleamed that Protestantism was there to stay, something King Philip and the Guises still could not accept even as entire countries officially embraced the new branch of Christianity.

It was a dramatic change from the unrelenting persecution that was standard for the reign of Catherine’s late husband, and Protestants celebrated as such. Naturally, the Triumvirate did not relent in their efforts to bring the Guises to power. They scored their own major victory when King Philip managed to woo Antoine de Bourbon with promises of restoring the lands lost to his wife’s kingdom of Navarre, promises he had no intention of keeping of course. Antoine cut ties to Protestantism, publicly aligned to the Triumvirs, and declared his opposition to the new edict, much to his wife Queen Jeanne’s chagrin.

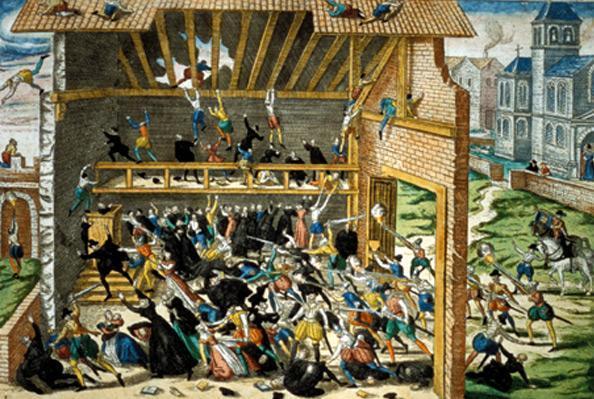

The pressure was building, and perhaps it was only a matter of time until it burst. On March 1, 1562, the Duke of Guise was traveling and stopped at the town of Wassy in northeastern France. The town laid on estates that traditionally belonged to the Guise family. While in town, the Duke attended Mass at a church. Even over the sound of the service, he could hear hymns being sung by Protestants from a nearby barn within the town’s borders, a clear violation of the terms of the new edict. The story of what happened next was contested in ways you might expect; the Duke claimed he was attacked while he was simply leading an investigation into an illegal gathering as was his right, the Huguenots told authorities they were the ones deliberately attacked. Whatever took place in Wassy that spring day, Guise’s men and the Huguenots took out their arms and fought. However, the battle-hardened Duke and his men had the advantage. Still, he would bear a scar from a cut to his face and some of his men were injured. But out of the town’s Huguenots, seventy-three men and one woman were dead and more than a hundred people were wounded, many shot while trying to flee the barn.

Back in Paris, a lawyer named Etienne Pasquier heard the news of the Massacre of Wassy and dreaded civil war. He wrote in a letter to a friend that he was certain the massacre would be “the beginning of a tragedy.” Indeed it was. The massacre was just a beginning to almost forty years of civil war, what historians call the French Wars of Religion. These Wars of Religion would consume the lives of Catherine and her beloved children.