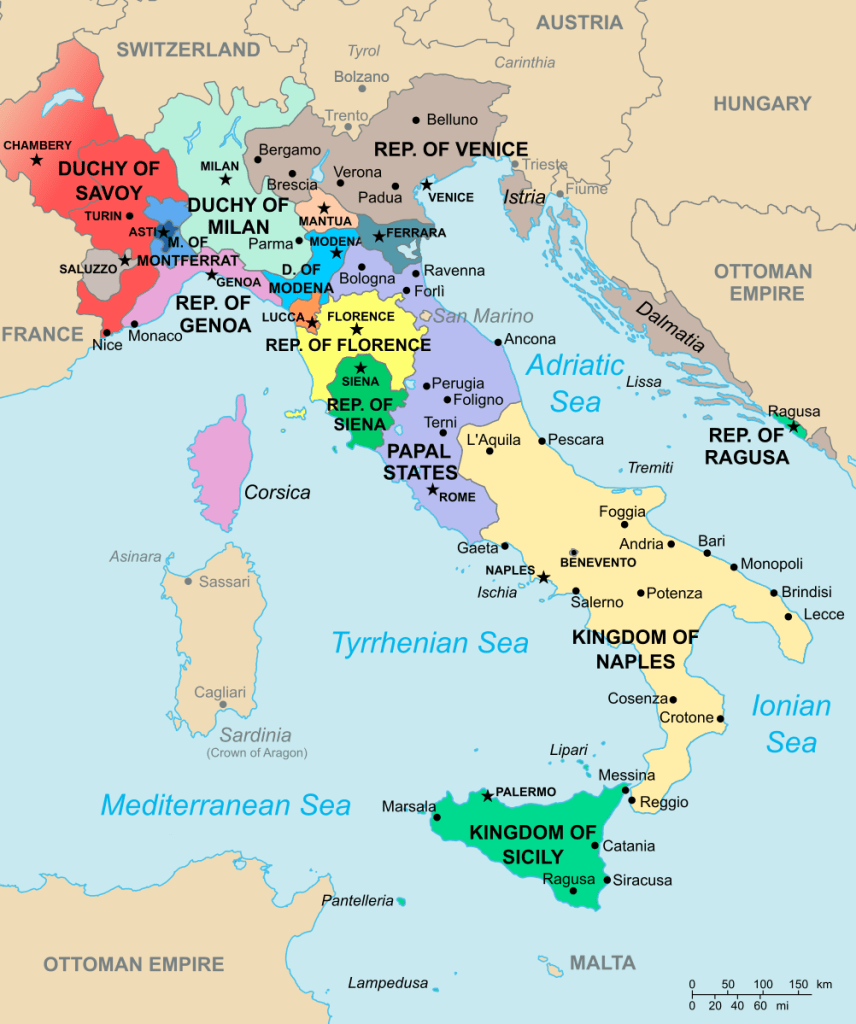

We step back from the Medici to look at Europe as a whole circa 1492. The balance of power is shifting and that means, for the Medici and Italy as a whole, the flood is coming.

A map of Europe circa 1500 (although it should be noted modern Spain was still administratively divided between the kingdoms of Aragon and Castile). Source: The University of Oregon.

Transcript

Apres moi, le deluge. This means “after me, the Deluge.” Depending on who you ask, the saying was spoken by King Louis XIV of France on his deathbed, by Louis XIV’s great-grandson and successor Louis XV, or by Madame de Pompadour, Louis XV’s mistress. There’s some debate over what it means, too, but the way I learned about the phrase was that it was Louis XIV predicting some disaster befalling France after his death, a disaster like maybe the French Revolution. One can certainly believe Louis XIV was enough of an egotist to think the whole show would fall apart after he left the stage, but the main problem with this interpretation is that there were over seven decades until the Revolution started. Honestly, it would have been much more apropos if Lorenzo de’ Medici said it or the Italian equivalent, which I think would be “dopo di me, il diluvio”, while he was dying.

In the years surrounding the time of Lorenzo’s death, events across Europe were coalescing rapidly, in a way that would shock not just the future of the Medici, but the future of Italy. So I’m going to pull the camera back quite a lot from Lorenzo’s deathbed, and take a tour of Italy and then the rest of Europe so we can see the storm clouds that are gathering on both sides of the Alps. I’m not going to talk about every single nation, just the ones that are going to be major players in the saga that’s about to begin.

Let’s start at the boot end of Italy with the kingdom of Naples. I should fess up and admit that I’ve avoided Naples because it’s got a complicated history. As you probably know, even the name of the place or whether or not we’re talking about one or two nations depends on what period of time we’re looking at. It’s been called the Kingdom of Naples, the Kingdom of Naples and the Kingdom of Sicily, the Kingdom of Apulia, the Kingdom of Trinacria, or even the Kingdom of Two Sicilies, a name that no matter how long I read about and research European history, never fails to give me a headache. However, Naples and its messy history is about to be at the heart of our story, so let’s get into it.

After the Carolingian conquest of northern Italy that we talked about way back in season zero and the arrival of the Arabs, a mess was made out of southern Italy. Sicily was ruled by an Islamic emirate, while the rest of southern Italy was a patchwork of territories controlled by independent city-states, the Byzantines, and small principalities that were the remnants of the old kingdom of Lombardy. Then along came the Hautevilles, the sons of a noble family from Normandy in northern France who came to the bloody battlefields of southern Italy to make a living as mercenaries. The Hautevilles proved to be masters of playing all sides against each other, until they ended up dominating southern Italy in their own right. On Christmas Day of 1130, the Pope finally agreed to make Roger II the king of Sicily. In exchange, Roger agreed that the kings of Sicily would hereafter be the vassals of the Pope. Now, of course, plenty of Popes claimed to be the overlord of all the monarchs of Christendom. But it was one thing for say the English to laugh off the Pope’s claims that he was above all secular rulers, it was another thing for a king right in the Pope’s backyard to tell the Pope off. So, flashforward a couple of centuries after the Hauteville line dies out and the crown of Sicily passes to the Hohenstauffens of the Holy Roman Empire, this is why the Pope felt justified in offering the Sicilian crown to a French prince, Charles of Anjou, albeit only if Charles of Anjou could conquer the kingdom in war. As we talked about in season one, Charles of Anjou did indeed win the kingdom, only for the prize to break apart when a French soldier assaulted a Sicilian woman, sparking the revolt known to history as the Sicilian Vespers. Charles of Anjou held on to Naples and the rest of southern mainland Italy, while Sicily went to a Hohenstauffen heiress, Constance, who had married the king of the Spanish kingdom of Aragon.

The Kingdom of Sicily remained under the control of the monarchs of Aragon, who also seized control of Naples in 1442 after the direct line of Charles of Anjou died out. Upon his death, King Alfonso I left the kingdoms of Aragon and Sicily to his brother Juan. However, he set up his only son Ferrante, who also happened to have been born out of wedlock with Alfonso’s Italian mistress, to become King of Naples. This is of course the same King Ferrante who was Lorenzo the Magnificent’s host.

After reigning for 35 years, King Ferrante died, less than two years after Lorenzo. Through sheer guile and the careful cultivating of alliances, he stayed in power. But the old claim of Charles of Anjou to Naples was still out, passing to Ferrante’s rival Rene of Anjou and eventually to the kings of France. This was the situation when Ferrante’s son became King Alfonso II. Luckily for him, Alfonso II was a talented general, something he proved in the war against Florence. Unluckily for him, he inherited his father’s notoriety but not his ability at diplomacy or public relations. On top of having a reputation for cruelty like this father, Alfonso was also infamous among his own people for his many bisexual love affairs. Among his lovers was a Neapolitan count Onorato Caetani, who was briefly married to Alfonso’s illegitimate daughter Sancha until the marriage was dissolved by Pope Alexander VI to free up Sancha to marry the Pope’s own illegitimate son, Gioffre Borgia. Onorato soon got a consolation prize by being allowed to marry Alfonso’s own half-sister. So, basically, Alfonso reportedly had a relationship with a man who was both his son-in-law and brother-in-law. Who says you have to go all the way back to ancient Rome to find historical incestuous soap operas?

Anyway, speaking of Rome, let’s go a little ways north. Innocent VIII had failed spectacularly to organize his crusade against the Ottoman Empire. Ironically, it was the fact that the Ottomans were driven off the Italian peninsula with relative ease that smothered any chance of a crusade. As I think most of us learned from our contemporary politics, governments aren’t terribly good at addressing threats that aren’t immediate, which the Ottoman Empire became agit again once it left Italy. What Innocent VIII did get was an Ottoman prince, Cem [Gem]. The Ottomans always had a bit of a problem with succession, since when a Sultan died his sons would enter a free-for-all over the throne. Sultan Beyezid’s brother Cem tried to snatch away the empire and failed and lived as a fugitive around the Middle East and eastern Europe until he ended up a hostage in the Pope’s clutches. Innocent VIII died just a couple of months after Lorenzo the Magnificent. Custody of Cem passed on to Innocent VIII’s successor, Alexander VI, or as you probably know him, Rodrigo Borgia. We’ll meet the Borgias later on, but for now let’s just say that when he became Pope the papal territories in the Romagna were still filled with petty aristocratic landlords who only paid lip service to papal sovereignty. And like Lorenzo’s great archenemy Sixtus IV, when Alexander VI looked at the Romagna he didn’t just see a feudal anarchy. He saw a potential kingdom his family could carve out with his support.

Then there’s Milan. You might remember I mentioned that the reigning duke was Gian Galeazzo and there was a power struggle between the young duke’s mother, Bona of Savoy, and his uncle Ludovico. Ludovico won. At the request of King Louis XI of France, Ludovico let Bona of Savoy quietly go into exile in her homeland. As you might expect from all the real-life and fantasy stories of a young heir being in the clutches of his wicked uncle, Gian Galeazzo himself was not as fortunate, depending on your point of view. He was left to a life of banquets, hunting, and sex with various mistresses in a kind of gilded cage while his uncle actually the state. But then, in 1494, Gian Galeazzo suddenly died at the age of 25. Some chroniclers suspected poison. While this was common enough in historical chronicles whenever royalty had an untimely or very convenient death, given the circumstances…perhaps he was poisoned. In any case, the duchy of Milan didn’t pass to Gian Galeazzo’s own young son Francesco, but to Ludovico himself. The problem was Gian Galeazzo had been wed to Isabella, Alfonso II of Naples’ daughter. It was bad enough that his daughter had been kept a prisoner of sorts with a husband who still managed to cheat on her constantly. How much worse was it that his widowed daughter was kept under house arrest in Milan and his grandson had been disinherited. In no small part because of this that the alliance between Naples and Milan, which had always been shaky, did not long outlive the great mediator Lorenzo the Magnificent.

Let’s look around Milan at the once great merchant republics of Genoa and Venice. Genoa especially has seen better days. It even lost its independence briefly to Milan. Although it did free itself from Milan, it also had lost its prosperous Black Sea port Kaffa and the Greek islands it once controlled to the Ottomans. As for Venice, it had already lost several of its holdings around Albania and Greece to the Ottoman Empire. Being hit hard by the same economic recession that was overcoming Florence, Venice was on the brink of another devastating war against the Turks.

Now it’s time to go past the Alps and to the western edge of Europe. Just before before Lorenzo died, the emirate of Granada in southernmost Spain, the last remnant of an Islamic empire that long ago covered most of modern-day Portugal and Spain, fell to the combined armies of the Christian kingdoms of Castile and Aragon. The two kingdoms were still administratively speaking separate governments and would remain so for a long time, but they had become unified in a very real way with the marriages of their monarchs Isabel of Castile and Fernando II of Aragon. With the fall of Granada, where once the Iberian peninsula was home to many different Christian and Islamic powers, all that was left now were the two united Spanish kingdoms and Portugal.

Over the mountains in the east was, of course, France. In the early 1400s, France was tethering on the brink of total conquest by the English. France started to recover its position as the century dragged on, and it was King Louis XI, the one who wrote so sympathetically to Lorenzo after his brother Giovanni’s murder, who finally brought the Hundred Years War to an end with a treaty that gave England generous cash payments and trade agreements. This caused Louis XI to brag that while his father had to defeat the English with an army, he could do it only with venison pies and good wine. Over the coming decades England would attempt to invade France again, and in fact the monarchs of England kept calling themselves the rightful monarchs of France until 1803, but effectively the existential threat England posed to France had finally ended since King Edward III first claimed the French throne back in the 1300s.

Louis XI, who was given the admittedly fantastic sobriquet of “Universal Spider” for his skills at diplomacy and outright manipulation, also put an end to another great rival of France, the duchy of Burgundy. For centuries, Burgundy had been ruled by a branch of the French royal dynasty, who through a series of fruitful dynastic marriages and political maneuvers managed to add most of the modern-day Netherlands and Luxembourg to their territories. These acquisitions made the duchy of Burgundy one of the richest nations in Europe, and a major menace to France that would side with the English when it suited it. Burgundy even came tantalizingly close to getting the Pope to recognize them as an independent kingdom, rather than just a duchy that was technically part of the kingdom of France. This is one of the great what-ifs in European history, namely what if France and Germany had a strong buffer state between them and a different geopolitical situation that didn’t allow for the kind of territorial disputes that would eventually play a large role in quite a few of the world-changing conflicts of the 19th and 20th centuries. But that’s not the world we ended up with. Instead, Charles the Bold, the Duke of Burgundy, let his boldness get him killed by Swiss mercenaries in a struggle against his neighbor the Duke of Lorraine. Louis XI quickly sent in his army to seize the duchy’s lands in what is now eastern France. He still lost the northern part of the duchy, comprised very roughly of modern-day Belgium, Luxembourg, and most of the Netherlands, to Charles the Bold’s daughter Mary of Burgundy and her new husband Maximilian von Hapsburg. What no one at the time could have known was that this was the set-up for centuries of bloody conflict, which will definitely have a bearing on our story.

But before we get to the Hapsburgs let’s stay a while with Louis XI. If you ever wanted to find a real-life Games of Throne character, you could do worse than the Universal Spider. Louis XI was ruthless in his politics and callous in his personal life. He schemed against his own father, neglected his first wife Margaret Stuart and had her poetry destroyed after her death, and was noted for his misogyny even in the fifteenth century, when is quite an accomplishment. About his own daughter Anne de Beaujeau, Louis complimented her by calling her the “least stupid woman I know.” He also absolutely despised his cousin, Louis d’Orleans, and deliberately forced him to marry his other daughter Jeanne, who was known to have been infertile, so Louis wouldn’t have an heir. Louis XI had left a France that was once again a great power and had no dangerous rivals at its borders, at least for the time being. But in his last years he feared his only son Charles, who was a sickly child, wouldn’t even live long enough to succeed him. So Charles was raised in an isolated chateau, his servants and tutors strictly screened by King Louis himself. This left Charles to grow up with chivalric poems and stories of his ancestors, especially of Charles of Anjou, who very nearly established a French empire that would have included most of Italy and the historic city of Constantinople. Since at this point the French monarchy didn’t allow women or anyone with a blood claim to the throne through a woman to inherit the crown, if Charles died, that meant the French crown would come down to the hated Louis d’Orleans. Did I mention Louis d’Orleans is a descendant of Valentina Visconti, the daughter of the Duke of Milan whose marriage into the French royal family I said would become a huge deal later? Yeah.

Now, let’s conclude our tour by going further east to Austria. We haven’t had the Holy Roman Empire play a role in our story for a while. That’s about to change, though, thanks to a family you might have heard of named the Hapsburgs. There had been a Hapsburg emperor of the Holy Roman Empire once before, Rudolph, in the thirteenth century, but he was just a compromise candidate, elected just because he wasn’t too powerful and the different factions were okay with waiting for him to die before they would fight for the imperial throne again. Also since the fall of the House of Hohenstauffen, very few emperors had the resources to impose their will that much on the various dukes and counts and bishops of the Holy Roman Empire. The story had changed by the late fifteenth century. Maximilian von Hapsburg was not just elected as emperor after the death of his predecessor, the emperor Frederick III, and the husband of the richest heiress in Europe, Mary of Burgundy, but from a cousin he inherited the regions of Further Austria and Tyrol. In particular, Tyrol had gold mines. And even after Mary of Burgundy died young in a horse-riding accident, Maximilian was still considered the co-duke of Burgundy. In a stroke, he had access to some of the few gold mines in central Europe and the tax revenues of one of the richest, most urbanized parts of Europe.

And what about the Ottoman Empire that seemed on the brink of conquering Italy? Well, besides duking it out with the Venetians over Greece, the Ottomans were done with Europe…for now. Their empire had reached a hard geographical border, in the form of the Carpathian Mountains, and a hard geopolitical border, in the form of the sometimes allied powers of Poland, Hungary, and the Holy Roman Empire. Besides, the Sultans had turned their attention south, conquering Syria, Palestine, and Egypt and trying to expand their sphere of influence over North Africa.

I hope you were paying attention because all this will be on the test. Seriously, though, the point is the Ottomans were distracted, France and the Spanish kingdoms were at the height of their powers and rid of any bad neighbors, and for the first time in centuries the Holy Roman Empire had at the helm an emperor with large enough an army and fat enough of a wallet he had a good shot of steamrolling over any princes of the empire who might defy him.

The game board is set. Now it’s almost time to watch the dominoes fall.