Even as a small child, Lorenzo had been thrust into the role of the public face of the Medici regime. Now an adult, Lorenzo’s own marriage to a Roman noblewoman from a clan claiming the Emperor Augustus and Julius Caesar as ancestors is a chance for the Medici to ascend even higher. Meanwhile, Piero is finally succumbing to his gout, just when both the domestic and foreign situations are starting to fall apart.

Transcript

Well, I know “Rising Sun” is probably one of the most obvious word plays you can make in this case, but it really is just…too relevant. Because Lorenzo di Piero di’ Medici was exactly that. From a very early age he was seen as the future of the family, so much so that his poor father Piero, through no fault of his own, was seen as little more than a placeholder, whose most important job was to live long enough for Lorenzo to reach adulthood.

The man who would become remembered as Lorenzo the Magnificent was born on New Year’s Day of 1469. His grandfather Cosimo was still alive when Lorenzo was a child. He remembered his grandfather with awe. However, he saw him rarely, and was instead much closer to his grandmother Contessina until her death in 1473. There is even a touching story of how, while at the Medici country estate at Cafaggiolo, Lorenzo and Contessina rode together on a donkey on their way to hear Mass at a country monastery. Despite the donkey’s small size and the fact that Contessina was balanced precariously on it, he was amazed that “she should be so much better at it than she thought possible.”

For his education, Lorenzo had some of the best teachers possible, naturally enough for a Medici. His chief tutor was Gentile Becchi, a priest and poet who no doubt inspired Lorenzo’s own dabbling in literature. Lorenzo also got to enjoy conversations with scholars and artists, including his grandfather’s own father Marsilio Ficino. From him, Lorenzo learned first-hand about Platonic philosophy. Lorenzo was a good student, although Gentile’s letters to Lorenzo’s father Piero suggest that Lorenzo wasn’t motivated just by a love of learning, but a desire to please his stern, overbearing father. In any case, Lorenzo was a bright student. He was also athletic, who loved as a child exploring the fields and forests around his family’s estates in the Mugello. He was also unlike his father healthy, although he did inherit his mother’s eczema, which would cause him to constantly seek relief by going to thermal baths.

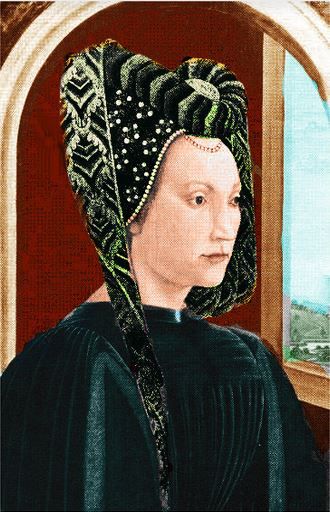

One thing Lorenzo was not blessed with was good looks, at least according to his own contemporaries. Lorenzo especially ran afoul of contemporary standards of beauty, which found him too swarthy. But honestly, if you’re been paying attention to the portraits I’ve been posting on the website, the men of the Medici family do not have an excess of handsome genes in the gene pool, to put it nicely, but maybe that’s just me. Here is a description from Miles J. Unger’s biography of Lorenzo, “Magnifico”:

As for Lorenzo himself, here is a description from Miles J. Unger’s biography“Above an athletic frame, bony and long-limbed, was a rough-hewn face. His nose, which was flattened and turned to the side as if it had once been broken, gave him something of the look of a street brawler, and the prominent jaw that caused his lower lip to jut out pugnaciously did nothing to soften this impression. Beneath heavy brows peered black, piercing eyes more suggestive of animal cunning than refined intelligence. Dark hair, parted in the middle, hung down to his shoulders, providing a stern frame to the irregular features. Even a close friend, Niccolo Valori, was forced to admit that nature had been a stepmother to him with regard to his personal appearance. Nonetheless,” continued Valori, “when it came to the inner man she truly acted as a kindly mother…although his face was not handsome it was full of such dignity as to command respect.”

Even meaner in describing his looks than this alleged friend of Lorenzo’s was Machiavelli. Machiavelli, who was a contemporary of Lorenzo’s, compared him in a letter to a friend to an unattractive prostitute he had sex with. Of course, this did not stop Lorenzo when he grew older from becoming a ladies’ man, and possibly not just that according to some people. But let’s hold off on a deep dive into Lorenzo’s private life as an adult for now.

As I mentioned before, Cosimo supposedly glimpsed Lorenzo’s potential even when he was a very young child. These claims might have been hindsight, but it is true that from very early on Lorenzo was entrusted with significant responsibilities. At only the age of five, he led a procession of adults and children to greet Duke Rene of Anjou at the gates of Florence and recited a list of memorized greetings. At six, while he was recuperating from eczema at a mineral bath, he was given the rather ironic title of “Lord of the Baths”, which meant he had to preside over parties and picnics with the children of Florence’s richest families. He was at least eleven when he was expected to communicate with and talk with clients. We know because we still have his first surviving letter, written in 1460 when he was eleven, which asks for a favor for a Chalumato from Arezzo. One year later, he wrote to his father, on behalf of a certain Griso who wanted a job as a a government notary. And when he was in modern terms a teenager, he was responsible for a diplomatic mission to no one less than the King of Naples and the Pope. There’s two conclusions we can draw from all this. One, Lorenzo was not being reared like the son of a banker or even a republican statesman, but like a prince, whose role in society was to lead without question.

Second and more personally…well, it is true that before the 20th century or so in the West our ideas of childhood and adulthood were very different. While today we don’t consider someone to really be mature until they’re 18 or in their mid-20s or possibly even later, people were expected to work or placed in roles of responsibility at what we would consider very young ages. Still, even for the era, Piero’s sickness and the lack of adult men in the main branch of the Medici family, besides Lorenzo’s spectacularly unambitious cousin Pierfrancesco, meant Lorenzo as a child had a lot of responsibility on his little shoulders, perhaps almost from the moment he became aware of himself and his place in the world. I agree with Lorenzo’s most recent English biographer Miles J. Unger that this must have all left a deep mark on Lorenzo’s psyche. No wonder he was so eager to please his father and why he lovingly described his mother Lucrezia as the person who helped shoulder his burdens.

We get another glimpse of how all this affected Lorenzo in a philosophical poem he wrote as an adult, “The Supreme Good”:

“I do not know of riches or honors sweeter than this life of yours – one free of all political intrigue.”

Throughout his life, Lorenzo enjoyed escaping from the city and spending at least a few days in the countryside. And as much as he was eager to be the public face of his father’s regime, once while on a state visit to the town of Pistoria, Lorenzo asked permission to also go to nearby Pisa and Lucca, admitting that while he would deal with business he also wanted an excuse to go fishing.

If Lorenzo did have pastoral fantasies about escaping to the countryside, life was if anything going to take him in the opposite direction. The Medici had risen high since his great-grandfather Giovanni di Bicci’s day, and Lorenzo’s parents Piero and Lucrezia had aspirations for the family to rise even higher. And one of the sure ways to go up even further on the social ladder, even today in some cases, is through a good marriage. Now Lorenzo’s sisters were engaged to marry into the usual banking and noble dynasties comprising the Florentine upper crust. Maria and Bianca were wed to the bankers Lionetto de’ Rossi and Guglielmo de’ Pazzi respectively. Lucrezia the Younger, whom in private life the family called Nannina to help distinguish her from her mother, married another member of a banking dynasty, Bernardo Ruccellai, who was also an accomplished humanist scholar and historian. But these were all just big fish in the Florentine pond. Lorenzo and his younger brother Giuliano would be paired with women from the wider world outside Florence. We don’t know for sure, but it seems like having ambitious matches for her sons were mostly if not entirely Lucrezia’s idea. Giuliano was engaged to marry the daughter of Iacopo Appiani, an accomplished general and the territorial lord of the city of Piombino near Siena. As the heir, though, Lorenzo was intended for an even grander match, namely Clarice (Cla-rr-isay) Orsini or Clarice in the English rendering.

Clarice was the niece of the cardinal Latino Orsini, one of the movers and shakers in both the Vatican and Rome itself. More than that, though, Clarice represented one of the most distinguished clans in not just the city of Rome, but all of Italy. The Orsini traced their ancestry directly back to the Julio-Claudians, the first imperial dynasty of ancient Rome, which would also mean they could put the first emperor Augustus, Julius Caesar, and even the Trojan hero Aeneas and the Roman goddess of love Venus on their family tree. Now if you’re an ancient history buff like I am, you might be thinking, wait, I’ve seen “I, Claudius”, didn’t the Julio-Claudians do a great job of wiping themselves out? Well, yeah, but there were a couple of survivors, specifically Augustus’ great-granddaughter Aemilia Lepida and the emperor Tiberius’ great-granddaughter Rubellia Bassa. We can even trace their descendants as late as the second century CE. So, bottom line, it’s not outside the realm of possibility. But it is worth noting that, much like how English people like to claim they can trace their families to the Norman Conquest and Americans love to talk about their Cherokee or Puritan ancestors, all the Roman noble families claimed to be descendants of one of the great families of the ancient Roman Republic. In fact, the Orsini’s own centuries-long, bitter rivals the Colonna family, also claimed they had Julio-Claudian blood in their veins. So that makes it rather unlikely. Still, though, personally I really want to believe that the Julio-Claudian tendency to murder themselves was so strong it resurfaced far in the future in the form of two of the most notorious feuding aristocratic clans in European history.

Anyway, the point is a marriage to someone like Clarice Orsini would have been a coup for the Medici. And as you might expect it wasn’t an easy achievement. In fact, it took a year and a half for both families to hash out the marriage contract. Lucrezia also insisted on getting a good look at her future daughter-in-law by visiting her and her family in Rome. We have a letter she wrote to Piero in which she describes Clarice like any expert appraiser would describe some objet d’art (objay dar), but also with a touch of intense maternal pride.

“We talked for some good time and I looked closely at the girl. As I said she is of good height and has a nice complexion, her manners are gentle, though not so winning as those of our girls, but she is very modest and would soon learn our customs. She has not fair hair, because here there are no fair women; her hair is reddish and abundant, her face rather round, but it does not displease me. Her throat is fairly elegant, but it seems to me a little meager, or to speak better, slight. Her bosom I could not see, as here the women are entirely covered up, but it appeared to me of good proportions. She does not carry her head proudly like our girls, but pokes it a little forward. I think she was shy, indeed I see no fault in her save shyness. Her hands are long and delicate. In short I think the girl is much above the common, though she cannot compare with Maria, Lucrezia, and Bianca.”

Once the marriage negotiations were finished for the 20-year-old Lorenzo and the 16-year-old Clarice, Lorenzo was greeted warmly by the Orsini. Uncle Latino started addressing Lorenzo as “our nephew.” Clarice was educated in Florentine manners by Piero’s brother-in-law Giovanni Tornabuoni, who was still managing the Medici bank office in Rome. He wrote glowingly back to Piero and Lucrezia, “Not a day passes when I do not see your Madonna Clarice and she has bewitched me. She is beautiful, has the sweetest of manners and an admirable intelligence. She has begun to learn to dance, and each day she learns a new one.”

To celebrate their marriage which was sealed by proxy, a joust was held in Florence on the morning of February 7, 1469, the same day the proxy marriage was to be carried out. The star of the show was Lorenzo, wearing armor and a helmet invoking the Roman god of war Mars. It was less an actual mock battle and more a celebration of the growing nostalgia for the golden age of medieval chivalry. It was also as clear a decoration as any that the Medici were no longer just another family of bankers. Most of all, Lorenzo would see the joust as a highlight of his life.

How, though, did he and Clarice feel about their marriage? We don’t know. We do have a dutiful letter Clarice wrote to Lorenzo about the joust:

“I have received a letter from you which was most pleasing to me, telling me of the tournament in which you gained much honour. I am most glad that you have been satisfied in a thing which gives you pleasure ; and if my prayers have been granted in this, I, as a person who desires to do something to give you pleasure, am well satisfied. I beg you to commend me to my father Piero, to my mother Lucretia, to Madonna Contessina, and to all others you think right. I commend myself to you. No more.”

Still, this letter came after Clarice refused to write to Lorenzo for several weeks, since he had not written to her and was busy preparing for the oust.

It is possible Clarice might have heard rumors about a certain woman, who might have been present at the joust and who could have been Lorenzo’s lover. She was Lucrezia Donati, a member of one of Florence’s oldest noble families and also a woman who was already married. But to be honest we don’t know for sure what her relationship with Lorenzo was, if there was any relationship. One of Lorenzo’s friends, the poet Luigi Pulci, did write a poem about the joust, in which Lorenzo honors Lucrezia Donati in the manner of knights to their ladies in the age of chivalry. Perhaps Luigi was hinting at something that was well-known among Lorenzo’s inner circle, or maybe he was just making a joke taken out of the unfounded gossip of the day. All we can say is that, in his own writings at the time, Lorenzo had nothing to say about his marriage except for one brief mention with zero sentiment, quote, “A bride was given to me.”

Whatever both their misgivings, the two had a formal marriage in Florence that year on June 4. The festivities were massive, with hundreds of barrels of wine said to be consumed at the house of Lorenzo’s uncle Carlo alone. There was, though, a severe rainstorm which caught many of the guests. Still, though, the weather could not spoil what was considered one of the best celebrates the city had seen in a generation.

As for Lorenzo’s father Piero, he continued relying on his sons and on Lucrezia to serve as his representatives. Piero was not only too sick to usually travel, but he increasingly became more reluctant to deal with other people, having always lacked the charisma of his father. Especially in his later years, Lucrezia, who as we’ve seen was perfectly qualified to run her own business affairs, became his business partner. She even handled some of her husband’s clients and the Medici bank’s customers. For example, she even helped Helena, the exiled queen of Serbia who had fled to Italy to escape the Ottoman invasion of her country, secure a loan from the Medici bank. This is not to say, though, that Piero and Lucrezia also seem to have genuinely loved each other. When Lucrezia fell ill, Piero wrote to her, “Have faith and obey the doctors and do not budge one jot from their orders, and bear and suffer everything, if not for yourself and for us, for the love of God who is helping you.”

But as much as he relied on his wife and sons Piero himself did keep track of politics and being involved in art patronage. While I did mention that it seems Piero viewed art more through the eyes of a businessman and banker than a connoisseur, that isn’t to say he wasn’t appreciative toward art and its creators. For example, Piero paid a pension to the sculptor Donatello, who was old enough to have worked for his grandfather Giovanni di Bicci. When Donatello died in December of 1466, Piero and his family along with the most popular artists of the city lead a funeral procession. Piero had even granted Donatello’s request to be buried in the Church of San Lorenzo, near the resting place of Cosimo himself. Piero also commissioned Luca della Robbia, who was the future president of the guild of sculptors, to carve some terracotta reliefs for the walls of his study in the Medici Palace. The artist Paolo di Doni’s paintings of birds and other animals decorated the walls of the Palazzo dei Medici. Paolo was also commissioned to make a painting commemorating a 1423 victory of Florence over the Sienese. Sandro Boticelli was a favorite artist too that Piero hired before he relocated to Rome where he would be one of the artists hired to work on the Sistine Chapel.

Piero also personally overlooked the artist Benozzo Gozzoli’s Adoration of the Magi, the murals that both depicted the Magi arriving to meet the infant Jesus Christ and also portrayed the Medici family themselves along with depictions of Piero and his children as well as the historic Council of Florence with the Pope and the Byzantine Emperor that Cosimo initiated. It seems that Piero was a bit of a micromanager, judging from the fact that it was Piero who told Gozzoli that he painted an angel who looked out of place in one of the scenes. The artist thanked him for his criticism – if his gratitude was genuine who knows but my bet would be probably not – and he agreed to cover up the angel with a fluffy little cloud.

By the time of Lorenzo’s marriage to Clarice, though, it was clear that Piero’s gout was finally catching up to him. Wracked with pain, he had himself carried to the family villa at Careggi, where he could barely lift his head off the pillow. As he lay dying, the corruption and unpopularity of his lieutenants, especially the statesman Tommaso Soderini, had come to a head. Piero was so horrified at the reports he received of how flagrantly his inner circle had been lining their pockets with state revenues that he considered allowing some of the exiles from the Party of the Hill to return just to serve as a check on them. However, he either decided it was a bad idea or was too weak to risk it.

At the same time, while Piero was slowly dying, a foreign crisis was about to rear its head. The region of the Romagna had long been a sore spot in Italian politics, since it was technically under the rule of the Papal States, but in actuality the territory was controlled by numerous feudal magnates who at most paid lip service to papal authority and were not at all reluctant to side with governments hostile to the Papal States. In this case, the signore of the Romagna city of Rimini, Sigismondo Pandolfo Malatesta, had died. He left behind a wife, Isotta, and a legitimate son in his infancy, but also an adult illegitimate son, Roberto. When Roberto violently seized control of Rimini, the Pope, seeing a chance to strengthen his grip on the Romagna, supported Isotta. Meanwhile Roberto got the support of Florence’s allies, Milan and Naples. The Republic of Venice, afraid that Milan might seize the opportunity to consolidate its influence in northern Italy, also threatened to intervene on Isotta and the Pope’s behalf .

Since the height of Cosimo’s power, the Medici had more or less near-total control of Florence’s foreign policy. However, the prospect of getting dragged into another pan-Italian conflict by the Medici’s ally Milan stoked serious resistance in the government for the first time since the heyday of the Party of the Hill. Either because of the pressure or because his fatal illness was affecting his judgment, Piero seriously gave some support to the faction in the government that wanted to break the extremely valuable alliance with Milan, even though such a decision would have likely left Florence dangerously isolated. This is when Lorenzo, who had always been loyal to his father’s political policy, stepped up and openly defied him. He wrote a series of groveling letters to Duke Galeazzo Maria of Milan, all but explicitly telling the duke that he only had to wait for Piero to die and the friendship between Florence and Milan would again be secure.

The duke did not have to wait long. On the afternoon of December 2, 1469, surrounded by priests, friends, clients, and his family, Piero had a seizure and then passed away. It was now finally time for the 20-year-old Lorenzo to sit on the invisible throne of the Medici, and he would have to do so at a time when confidence in his father’s cabal was sinking and when the political situation in Italy was again threatening to boil over. It was time to see if Lorenzo would live up to his family’s expectations.