Make a one-time donation

Make a monthly donation

Make a yearly donation

Choose an amount

Or enter a custom amount

Your contribution is appreciated.

Your contribution is appreciated.

Your contribution is appreciated.

DonateDonate monthlyDonate yearlyTranscript

Let’s talk about the Renaissance. Because the Renaissance was a truly international movement, and not at all the exclusively Italian movement we tend to think of it as, to talk about it it’s almost impossible not to jump around in space and time. So, for the sake of trying (possibly in vain) to keep things tidy I split my discussion of the Renaissance in two. First, we’ll talk about the old, how the Renaissance looked back into the past. Second, we’ll get into the new, meaning how the Renaissance looked forward.

But first to talk about how the Renaissance was, by definition, a purported “rebirth” of the classical past, we’ll have to actually travel back to the past. [TARDIS Noise] So when this relatively new monotheistic religion called Christianity became the state religion of the Roman Empire in the fourth century, much to the surprise of many people at the time, there were tensions between Christianity and the old polytheistic culture. Tertullian, who has my vote for grouchiest of the church fathers, wrote in his treatise Prescription Against The Heretics, “What has Athens to do with Jerusalem?” And Jerome, who was chiefly responsible for the Latin translation of the Old and New Testaments that would become the official version of the Bible for the Catholic Church, the Vulgate, claimed he had a dream where no one less than Jesus Christ himself put him on trial and accused him of being a Ciceronian, not a Christian.

In fact, if we skim accounts of the fourth and fifth centuries, particularly how the more moderate Christians in the Roman Empire who actually wanted to co-exist with the polytheists lost out to the hardliners who ended up getting the emperors to outright outlaw paganism, we might think Christianity purged the old pagan culture. We might even assume it was a lot like the Taliban in the present day destroying Buddhist monuments in Afghanistan or ISIL destroying the ruins of Palmyra. And indeed there were cases where Christians, especially the violent, fanatical mobs led by radical monks and priests that plagued the empire in the second half of the fourth century, did engage in similar acts of murder and vandalism. Many know about the brutal murder of Hypatia, the mathematician and Neoplatonic philosopher, in Alexandria just because it was thought she was an enemy of the city’s bishop. But there were plenty of less well-known events, like an Egyptian temple dedicated to Ramesses II, which was vandalized by Christians with crosses and graffiti. Nor could the Christian emperors resist the temptation to put the squeeze on the beleaguered pagans for some quick cash. Even under the first Christian emperors who at least told the public they simply wanted polytheists and Christians to get along, the government would sometimes liquidate pagan temples and their treasuries for money or convert the buildings into Christian churches.

But on the whole, while the hardliners did eventually get the government to back their campaign to drive the pagans underground, there was much less support for the idea of a Cultural Revolution, ancient Christianity style. For starters, the old gods were just too ingrained in the culture to be easily exorcised. The planets, constellations, and the names of some months were named after the gods and other figures from Greek and Roman mythology. And, with the exception of a minority of languages including Portuguese, modern Greek, and Icelandic, the days of the week in modern Indo-European languages still refer to the Greek and Roman gods or their closest equivalents in other cultures, even after two thousand years of Christianity. Also, while Christian authorities happily exploited the growing hostility toward paganism to fill their pockets, they were also surprisingly aware of what we would call cultural heritage and preservation. The Christian emperors would occasionally issue proclamations against Christian mob violence and defending particularly ancient and esteemed temples from being vandalized or looted. Alarmed by how the people of Rome were scavenging building materials from the ruins of the now decayed city, no one less than Pope Gregory I ordered that even the remains of pagan temples and statues be protected.

But what probably did the most to save the pre-Christian heritage of the ancient world was Christianity’s first public relations issues. There were those among the Church Fathers who did envision a complete break with the past, like the grouchiest of the Church Fathers, Tertullian, who famously asked, “What has Athens to do with Jerusalem?” There were also those like Jerome, who reportedly had a dream where no one less than Jesus Christ himself put him on trial and accused him of being a Ciceronian, not a Christian. These were the minority, however. Painfully aware of how their religion was seen as just a fad among women and slaves, the early Christians knew their best chance of survival lied with appealing to the educated Greek and Roman elite. And you didn’t do that by telling them that they’d have to throw out their copies of The Odyssey and the plays of Sophocles and instead be happy just reading the Psalms and the sermons of John Chrysostom.

Finally, it helped that the old gods were not often seen as a threat. There were early Christian writers who thought the gods were demons, and of course people thought the old temples were haunted. Others, however, cited the famous fourth century BCE Sicilian philosopher Euhemerus, who argued that the stories of the gods were just based on legendary kings, heroes, and scholars from the distant past. Euhemerus’ ideas were so long lasting and so widespread even in the Middle Ages it was taken for granted that the pagan gods were historical figures who lived far back in the deepest mists of time at more or less the same time as the patriarchs of the Bible. So the kings of England traced their genealogy all the way back to Woden or Odin, who they thought of as a prehistoric king – and, yes, this means Queen Elizabeth II is technically a distant descendant of Odin. Also the Franks, the people who gave France its name, claimed they were descended from another refugee from the city of Troy after the Trojan War, named – just guess – “Francus.” Medieval writers would describe Mercury as a great sage who invented the first alphabet, Venus as the world’s first courtesan, Atlas as an early astronomer, and Saturn and Jupiter as renowned kings of the island of Crete.

So, if the gods were just legends that got twisted in time into gods, there was no harm in writers and artists using them for allegorical purposes. As Jean Seznec put it, “The pagan divinities served as vehicle for ideas so profound and so tenacious that it would have been impossible for them to perish.” The typical educational curriculum, especially in Italy and the Byzantine Empire, still involved learning rhetoric by writing speeches coming out of the mouths of mythological figures. Writers and scholars didn’t even have any problems mixing and matching Christian and pagan figures, even comparing Jesus himself to the mythical musician who returned from the underworld, Orpheus. To further quote Seznec: “In this strange game of changing places, Christ may become a Roman emperor, an Alexandrian shepherd, or an Orpheus, and Eve a Venus. On the other hand, Jupiter may appear as one of the Evangelists, Perseus as St. George, Saturn as God the Father. But no god is now represented in his traditional form as a divinity. The mythological heritage…has so disintegrated that in order to take stock of its remains, we find it necessary to distinguish between a pictorial and a literary tradition which had become completely separate. Neither tradition, by itself, was able to keep intact the memory of the gods…Thus the Renaissance, rightly seen, is in no sense a sudden crisis; it is the end of a long divorce. It is not a resurrection, but a synthesis.” Probably a good example of this in action was what happened in the German city of Augsburg in the early sixteenth century, when a statue of a saint was replaced with a statue of the god Neptune. The local church authorities were enraged and went over the heads of the city elders directly to the Holy Roman Emperor, who declined to lift a finger to help them.

Now this isn’t to say that the Renaissance didn’t see a massive change in how people looked at the gods and myths of antiquity. Much of the knowledge of the Greek-speaking East had been lost or had become obscure in the Latin-speaking West since the collapse of the Western Roman Empire. One of the many consequences was that artists and writers in western Europe were familiar with Greek and Roman mythology as filtered through Arabic sources. So when medieval Latin Europeans drew, say, the hero Perseus they thought of him wielding a scimitar while Hercules would often be seen sporting a turban. What the scholars and artists of the Renaissance did was start going back to the actual ancient sources when they described or depicted the old gods and stories, giving them the forms we would still recognize today.

Part of what made this happen was one book, Boccaccio’s Genealogy of the Gods. Commissioned by King Hugh IV of Cyprus, it was a huge multi-volume work that tried to untangle the complex and often contradictory family relationships between the Greek gods. The work was so taxing, in fact, that although an initial version of the book was published in 1360, Boccaccio kept having to go back and make corrections and expansions until his death 14 years later. Boccaccio did draw on some medieval sources, but he also made the almost revolutionary choice to actually go back to the original Greek texts like Ovid’s Metamorphoses.

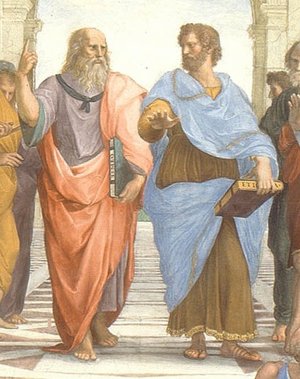

However, it wasn’t just that Boccaccio made “check your sources” fashionable again. Greek texts like the kind Boccaccio used were becoming more available by the second half of the fourteenth century. One person who played a key role in this was a native Greek. Georgios Gemistus was born in Constantinople sometime between the years 1355 and 1360. Although he was an active and well-respected member of Byzantine civil society and even enjoyed the favor of the emperor, Georgios Gemistus was so fascinated by ancient Greek philosophy the Church suspected him of heresy. In fact, Gemistus started going by the pen name Pletho, which he came up with just because it sounded similar to the name of his idol Plato. Also, in his book On The Laws, he made the radical proposal that the beleaguered Byzantine Empire should abandon Christianity altogether and instead embrace a new religion that would combine ancient Greek polytheism and Platonic and Stoic philosophy with a little bit of the teachings of the great religious prophet Zoroaster mixed in. Needless to say, he only shared the book with close friends and, after his death, the Patriarch of Constantinople had it burned. We only know it existed at all because Pletho wrote a summary of it himself that was kept by one of his Italian disciples, Cardinal Bessarion.

It was this outsider who was a dedicated fan boy of antiquity who helped bring the ancient Greek world to modern Italy. I’ll revisit this more when we talk about the life and times of Cosimo de’ Medici, but Pletho eventually winded up in Florence as part of a Byzantine delegation to negotiate the reunification of the Roman and Orthodox Churches in exchange for the Pope to whip up a new crusade to save what was left of the Byzantine Empire from the Ottoman Turks. It…didn’t work, but Pletho and Cosimo did meet, and Cosimo bankrolled Pletho’s idea for a regular symposium, the Platonic Academy, which met for many years in the Medici villa of Careggi in the suburbs of Florence. To his eager students, Pletho lectured on the works of Plato, who had largely been forgotten in the west. One academic also sponsored by Cosimo and inspired by Pletho’s lectures, Marsilio Facino, taught himself Greek and went on to translate and write scholarly commentaries on the complete works of Plato and the writings of the Neoplatonic philosopher Plotinus. The knowledge of ancient Greek Pletho and Facino spread also allowed people to not just look at the ancient philosophers and poets, but also at the foundational texts of the Christian religion. Nor was ancient Greek the only avenue for scholars to get at the Bible. Less than a century later, a scholar native to the Black Forest region of Germany, Johann Reuchlin, studied ancient Hebrew with the help of Jewish rabbis and scholars. Taking his insights to the wider European community and fighting against the inevitable anti-Semitic backlash, Reuchlin published the first Hebrew dictionary and grammar in 1506. Almost immediately, scholars outside the Jewish community seized upon this resource to look at the original texts that comprised Christianity’s Old Testament. Whether they preferred to study old Greek literature or the Hebrew Bible, these people deliberately thought of themselves as humanists. The term came out of old student slang used at universities, derived from the Latin term studia humanitatis, meaning the “liberal arts”, which itself came out of the writings of the Roman political and orator Cicero. The 19th century historian Jacob Burkhardt described the humanists of the Renaissance this way: “They were a crowd of the most miscellaneous sort, wearing one face today and another tomorrow; but they clearly felt themselves, and it was fully recognized by their time that they formed a wholly new element in society.”

If all this had happened just a couple of centuries before they really did, the impact might have been way smaller, or at least taken much longer to spread out. But this all coincided with an exciting new development: the printing press. Of course, printing had been a technology used in East Asia since the eighth century CE, but a German goldsmith spontaneously designed his own functional printing press by 1439. While of course there were diehards like the Duke of Urbino’s librarian Vespasiano da Bisticci who stubbornly insisted that an old-fashioned handwritten book was far superior to these newfangled printed books, the printing press did at least make it much easier to become part of a thriving network of scholars. To give just one example, in 1484 a printing press in Florence produced 1,025 copies of Plato’s Dialogues in the one year that it would have taken a scribe to make a single copy of a book. Maybe more importantly, it made it possible for enterprising scholars to publish critical editions of key texts, whether the New Testament or Homer’s Iliad, with footnotes, commentaries, and parallel texts putting up the source material and translations together side by side. The important takeaway is that the story of classical scholarship in the Renaissance isn’t one of groundbreaking individuals who just suddenly decided, hey, it would be nice if we reintroduced Plato to western Europe. Instead, it really is the story of how a combination of cultural factors, helped along by a brand-new technology, led to the creation of a powerful and wide-reaching intellectual network. Believe it or not, the Middle Ages had their intellectuals and books written to be used as textbooks and scholarly sources too. What had changed was it was now much easier to get the resources or connections you needed, whether you wanted to teach yourself Hebrew for your own biblical studies or correspond with someone who had just discovered a manuscript with some lost ancient Greek plays. It really isn’t all that dissimilar to the impact the Internet had on the spread of knowledge, although I don’t think Renaissance scholars ever had to try to get an article that’s behind a paywall and you couldn’t even get it through most university libraries.

Anyway, the fad for primary sources had deep roots long extending past the invention of the European printing press. These roots stretched back to the decline of scholasticism, the dominant philosophy of medieval Europe, which stressed looking to the accumulation of commentaries on the source across generations rather than the original source itself. To give an example, in 1496, the English priest John Colet scandalized his contemporaries when he preached on Corinthians, and, instead of just referring the Latin commentaries, he cited the original Greek texts. I’ll get more into Scholasticism and its downfall next episode, because I suspect this episode will already run too long. Who knew talking about the Renaissance would get so complicated?

Anyway, another reason was society getting richer and messier and the Investiture Controversy, both of which we talked about back in season one. Both defenders of the rights of the Holy Roman Emperor to rule over Italy and the people serving the growing commune governments were drawn to the old Roman law books and the ideas on politics laid down by Aristotle, who unlike his teacher Plato was still familiar to westerners. This interest naturally led a demand for revised collections of Roman laws as well as a new Latin translation of Aristotle’s works which were distributed to different law schools and universities across Europe in the eleventh and twelfth centuries. The Romans might not have been all that great at philosophy or culture, but they were fantastic lawmakers, leaving behind a law code that was simple but precise, perfect for an urban society. This, coupled with Aristotle’s basic idea that human beings were political animals that fundamentally act rationally in self-organized societies, might as well have been tailor-made for the growing class of professional civil servants, rich merchants, and lawyers in Italy. These men appeared not just in city-states like Florence and Venice, but also in sophisticated royal courts like that of King Robert I of Naples. They had the leisure, the education, the money, and the connections to sponsor scholars, writers, and artists, and even dabble in research and art themselves. Their wives and female relatives did this, too, even if for obvious reasons it was harder for them to have the liberty and independence to do it, and usually they were widows or nuns. But I’ll go into more detail next time when I delve more into patronage in the Renaissance and talk about what the Renaissance meant for women, or at least upper-class women.

Tracking down old manuscripts, locked away in dusty old monasteries across Europe and the Middle East or brought west by Greek refugees fleeing the spreading Ottoman Empire, even became a favorite hobby of these men. The Duke of Urbino, Federigo de Montefeltro, started buying books as a boy. He kept thirty and more scribes employed and spent over 30,000 ducats on his own manuscript collection. A few, like the Florentine bibliophile Niccolo Niccoli, even made hunting down and copying manuscripts and editing the texts to fix errors made by copyists and divide them into sections and chapters a full-time profession. Patrons, including Cosimo de’ Medici, paid him well for his services, and it was Niccolo Niccoli who managed to find surviving copies of two pivotal works from antiquity, Pliny’s Natural History and Ptolemy’s Geography. His clients were, if anything, even more hungry for great lost books than he was. One of his correspondents wrote to him:

The bug has bitten me and while the fever is on it helps and pushes me. Please send Lucretius, the little books of Nonius Marcellus, the Orator and the Brutus – beside I need Cicero’s Letters to Atticus.”

This hunt for original texts had more consequences than even I could probably list here. Book collectors after their deaths often left their collections behind to universities or the public, establishing some of the oldest secular libraries in Europe. It enabled scholars to correct mistakes that had built up over centuries of being copied over and over again by overworked monks. And it enabled maverick scholars to overturn once unshakable assumptions. The most famous example of this is the case of the Donation of Constantine. Throughout much of the Middle Ages, it was believed that the first Christian emperor, Constantine I, had in his will granted political power over all of Italy to the Pope. It was frequently cited to justify the continued existence of the Papal States and was used by Guelphs in their argument that the Pope, not the Holy Roman Emperor, was the true master of Italy. The priest Lorenzo Valla actually wasn’t the first person to ever question its authenticity, but he was the first to basically nuke the document from orbit by examining the language of the document, looking at historical contexts, and just invoking simple logic. Nor was Valla humble about it. At one point after laying out the case for how absurd it would be for a Roman emperor to just handover the heart of his empire to someone else, he writes:

“But it is past time, for the sake of brevity, to give my enemies’ cause, already struck down and mangled, the mortal blow and to cut its throat with a single stroke.”

This is by far the most famous example, but it isn’t the only one. Elsewhere Valla would also critique nothing less than the Christian concept of the trinity. While he didn’t reject it outright, he did write that the theology around the trinity owed a lot to the bad Latin translations of early Greek Christian texts. Colucci Salutati proved that the author of the Commentaries on the Gallic War was none other than Julius Caesar himself. In 1516, the Dutch theologian Erasmus even dared to publish his own Latin translation of the New Testament which included annotations and corrections of the Vulgate, the old fourth century CE translation which was the only version the Catholic Church recognized as legitimate. Some of these corrections undermined the very basis of theological ideas the Catholic Church had held for centuries.

But it wasn’t just about the gods of Olympus or preserving and spreading the literary and intellectual achievements of the ancients. Soon enough, it also became about a whole new – or maybe very old – way of looking at politics and one’s role in society. Look at Dante’s political treatise, On Monarchy, where he argued in favor of the Holy Roman Emperor’s authority over Italy. No doubt he was embittered by his experience of being exiled from his beloved homeland of Florence, just because he backed the wrong faction at the wrong time. But, deliberately or not, Dante also made a much more profound case. Essentially he argued that the ideal state for all Christendom was to be ruled by one government under one emperor. The reason Christendom was riddled with city-states going to war against each other and people like a certain Italian poet being exiled just because of their political affiliations wasn’t because of acts of God or because people are inherently sinful. It was because there was no strong emperor to help ensure peace and unity. But it was possible to go back to that better state of things, through the actions of the people themselves.

These political ideas, drawn out of antiquity, really began to coalesce under the humanists, arguably starting with Francesco Petrarch in the fourteenth century. Born the son of a civil servant and merchant in Florence, Petrarch was pressured by his father into going to school to become a lawyer and civil servant. However, after being deprived of an inheritance through legal chicanery, Petrarch developed a distaste for both politics and the law, and instead devoted himself to the life of the mind. Today he’s mostly famous for the love poems he wrote to his unrequited love Laura, who was likely a French noblewoman who was an ancestor of the Marquis de Sade, so much so the term “Petrarchan love” has entered the English language. But Petrarch was also a prolific letter writer and joined the fad of collecting manuscripts early on, discovering a manuscript preserving Cicero’s letters to his friend Atticus. Although Petrarch did have some criticisms of his hero, he was struck by how Cicero was both active in politics and was a great philosopher. Whatever Cicero’s flaws, and Petrarch was fully aware of them, he did gleam in Cicero the sort of man the Italian city-states needed. It wasn’t someone who shut themselves away from society generally to dedicate themselves to spiritual and intellectual matters, like nuns and monks did, nor was it a leader who was skilled in battle and at being a courtier in royal courts but was undereducated, if not genuinely illiterate, like so many nobles especially in northern Europe. Instead, it was a true statesman of the Greek and Roman mold, who did not keep political, intellectual, and spiritual matters separate, but instead appreciated how they were all interconnected.

Like Dante, Petrarch also saw antiquity as a better time, superior to his own. In fact, it was Petrarch who coined the phrase, “Dark Ages.” In his letter to posterity, Petrarch writes, “Among the many subjects that interested me, I dwelt especially upon antiquity, for our own age has always repelled me, so that had it not been for the love of those dear to me, I should have preferred to have been born in any other period than our own. In order to forget my own time, I have constantly striven to place myself in spirit in other ages, and consequently I delighted in history.” Nor was he alone in having that sentiment among the huumanists. Writing a century later, the Florentine architect Filarete wrote, “I ask everybody to abandon the modern tradition. Do not accept counsel from masters who work in that tradition. I praise those that follow the ancient manner of building.” Just keep in mind that when he says “modern tradition” he means what we would call “medieval.”

Humanists following Petrarch’s footsteps took this new view of human nature and human agency over the quality of their own societies even further. Take, for example, Pico della Mirandola. A precocious and quite possibly unstable genius born to the ruling family of the duchy of Mirandola in north-central Italy, at just the age of 23 he published 900 theses written defending the positions of various famous philosophers and religious leaders and groups throughout history, including Plato, Pythagoras, the Jewish Kabbalists, the Prophet Mohammad, Zoroaster, and Paul. Pico even announced he would hold a public debate defending all 900 theses in Rome and offered to pay the travel expenses of anyone who would agree to debate him. In fact, it’s possible that Pico seriously expected that his debate would become such a momentous event it would lead to the mass conversion of the Jews to Christianity.

Pope Innocent VIII personally intervened and stopped the debates. About Pico, he grumpily said, “This young man wants someone to burn him one day.” A papal commission censured thirteen of his theses, and later on his entire 900 Theses would earn the distinction of becoming the very first book universally banned by the Catholic Church.

In any case, Pico also wrote a speech that he planned on accompanying his great debate in Rome. His “Oration on the Dignity of Man” rejected the Christian and Platonic view of the material world as corrupt and corrupting and the idea that humans are tainted by sin. On the contrary, humans are dignified and even made godlike by their unlimited freedom of choice. Pico even goes so far as to reinterpret the Fall as described in the Book of Genesis not as an act of disobedience against God, but as the inevitable cosmic conflict that happens between humanity’s attraction to sensuality and its spiritual nature. To emerge triumphant from that conflict and become one with God, a person had to pursue the liberal arts, in order to achieve a better understanding of not only the universe but also the self. Even more radically, Pico argued that all good ideas should be considered to have some legitimacy, no matter what culture or religion they sprung from, and there should be no compulsion in belief. Truth should and always would be arrived at through rigorous debate.

So there’s lots more I can cover, but I don’t want this episode to turn into something like Pico’s 900 Theses, so I’ll leave it there. But to summarize, humanism wasn’t an organized movement. Nor should we think of the phrase “secular humanism” when we talk about Renaissance humanism. Very few if any humanists from this period can be interpreted as calling for an alternative to Christianity, at least openly (and we should probably keep in mind historians today would probably assume Pletho was a typical Christian if he himself hadn’t summed up his own pro-Olympian god views in a document that escaped burning). It is true later on the Protestants would find a lot to like in the humanist insistence on going back to the original sources, inspiring Catholic reformers like Erasmus as well as pioneering Protestants like Martin Luther alike to claim that they merely wanted to go back to a more authentic Christianity that existed in the time of the Church Fathers. As the name “Renaissance” itself suggests, this was about trying to find better blueprints for life, religion, and society in the past.

However, the humanist reconstruction of the ancient world did bring about a lot of fundamental changes in how people viewed themselves and the world around them, changes that laid the groundwork for the world we live in today. And it had much deeper consequences than just the fact that, in the sixteenth century, parents starting giving their kids lovely names like In the sixteenth century people started naming their children Flavia, Livia, Hector, Julius Caesar, and Achilles. Like Aristotle’s political animal or Cicero the philosopher-politician, the idea that human beings had agency over their own lives and the societies they lived in became widespread. Further, for the humanists, people weren’t depraved because of the curse of Adam, but instead, through their own actions and behavior, they could become like animals or become dignified beings. Indeed, unlike with the medieval mindset, one’s place in the community was no longer determined just by one’s baptism into the church, but by one’s contributions to social and political life. If you could sum up how humanism and its rediscovery of antiquity caused the medieval worldview to crack and crumble, you could say it was because the humanist interpretation of the ancient world led to an understanding of humanity that was mostly independent of Christianity, as much as the humanists themselves still would have thought of themselves as Christians. To sum it up, humanists ended up erecting a stronger barrier between social and religious experience, between the natural and the supernatural, and between civil morality and religious morality.

Next time, I’m going to talk more not just about how the Renaissance changed, well, everything about mainstream philosophical thought, but also how the same era saw revolutions take place in the visual arts and music.