In our inaugural episode and the first part of our prelude season, we look at how northern Italy went from being a single kingdom to a region full of small, rival states, a cutthroat environment in which families like the Medici would nonetheless thrive in. Join us as we look at how urban prosperity, a series of invasions, and a scandalous teenage pope all played a part in making northern Italy a shattered and divided kingdom under the weak sovereignty of a faraway emperor.

Transcript

In the fall of 476, an honored prisoner arrived at a seaside fortress on the Bay of Naples, today called the Castel del’Ouvo, or in English, Egg Castle. The prisoner is well guarded, even though he’s only 16 years old, and he may have walked into his new home while dressed in silk robes. What he felt in that moment, we cannot say.

Maybe he felt something like grieving or rage against his captives, or some mixture of both. Personally, though, I would guess that he felt overwhelming relief. In any case, the Castel del’Uovo was built in the first century BC, which were much better times for the Romans than the era the teenager found himself born into. Originally, it was intended to serve as a luxurious vacation villa right in the heart of the Roman Republic’s hottest vacation spot, the region of Campagno, right on the Bay of Naples. Since then, much like the declining empire of the Romans itself, the Vila became much less like a pleasant beach house and much more like a military barracks.

In fact, the fortress still exists today and looks like a humorless and featureless leviathan of stone rising out of the sea. It was this place that, as far as history knows, would be the forever home of Flavius Romulus Augustus, better known to history by the diminutive Romulus Augustulus. Little Augustus. He had been propped up on the throne of the Western Roman Empire by his father, reigned but not ruled for about a year, and then the German General Odoacer quietly shipped him off to the sombre palace where, as far as we can tell, he lived out his entire life behind walls of stone. Whether you’re of the opinion that the last emperor of the Western Roman Empire was actually Romulus Augustulus or the exile Julius Napos, who kept claiming the title from his exile in modern day Croatia until his assassination.

There’s no debate that what the man who got rid of Romulus Augustus became was the first Rex Italia king of Italy. Of course, Odoacer held the title just at the behest of the one Roman emperor left standing, Zeno of the Eastern Roman Byzantine Empire. At least that’s what the enragement was on paper. In reality, Italy itself had joined many of the former provinces of the Western Roman Empire in becoming new, independent kingdoms under German dynasties.

Wait a minute. You might be wondering, what does any of this have to do with the Medici? Well, nothing directly, but the story of the Medici is intertwined with that of Italy, especially with Italy’s existence as a collection of city states, duchies one kingdom and one theocracy, more often at war with each other than not. Also, for the purposes of our narrative, I think it’s a worthwhile starting point for our story. It’s certainly a neglected topic, worth exploring, at least in my experience. Even college level Intro to World History courses skim over this entire period.

So you have the Western Roman Empire collapsing, and when you catch up with Italy again, it’s already the 14th century, and Dante has finished writing his Divine Comedy. We’re about to get started on the origins of the Renaissance. So for that reason, and because I think it makes for a nice, serious, messier narrative, let’s start our story in the Italy of the so-called Dark Ages. Now, I suspect, especially if you have already read a lot of history or listen to a lot of podcasts like this one, you already know that there’s been a lot of pushback against the term Dark Ages, because, as the historian Constance Breton Buschard puts it, it carries, quote, a tone of moral judgment. Even then, I’m sure the term Dark Ages conjures up images of Mad Max medieval style.

Now, it is true that the collapse of the Western Roman Empire hit the more rural, less prosperous northern peripheries of the empire hard Britain especially. We don’t know much about what it was like to live in Britain after the Roman army evacuated island in 409 because of a lack of written sources. But archaeology has filled in some of the gaps. Currency almost disappeared completely, no buildings made with mortar were constructed, and apparently not a single pottery producer was still working after the year 500. Also, Londonium, modern-day London, once the largest city in Roman Britain, became completely abandoned for at least almost a century. Italians experienced the end of the Western Empire differently, at least somewhat. It wasn’t like in Britain or most of Gaul, where suddenly, instead of actual professional bureaucrats and magistrates running things, you had to work for a local warlord. And that was if you were lucky. If you weren’t so lucky, he would take you or a family member for ransom or sell you into slavery instead. Sure, if you are a medieval Italian living in the city and quite well off, even you might find it way too expensive to buy precious stones or silk or even certain spices like your grandparents used to be able to in the days of the empire’s globe-trotting, super-rich who, for example, might own homes in Milan and Rome.

The days when you could own a house in North Africa and a farm and some vineyards in Portugal were long gone. And Rome was a much smaller place than it used to be, having possibly lost as much as nine-tenths of its population out of something around 800,000 people over the course of the painful and violent fifth century. But maybe your favorite local merchants still have some trade contacts in Antioch or Alexandria or any of the thriving cities in the Middle East, which was still the richest region of the Mediterranean world and safely still united under the rule of someone named Emperor of the Romans. And if you lived in Rome especially, politics probably didn’t look all that different. Remember Romulus Augustulus was just quietly shipped off and replaced by someone else.

Sure, the new guy was German and called himself a king rather than an emperor, but he was thoroughly Romanized and Italy had been practically run by Germans for decades anyway. Even the Senate of Rome was still having its meetings like always. Sure, they were basically a glorified city council by this point. But that’s what they had always been for as long as anyone could remember, anyway. Even after Odoacer was overthrown and killed by Theodoric, another Romanized German who hailed from a people called Ostragoths, it was still a new boss same as the old boss situation under the king history would remember as Theodoric the Great.

The old imperial bureaucracy even remained mostly intact. The good times never last, though, especially if you’re talking about the sixth century in Europe. Ironically, it would be the mission of the Byzantine Emperor Justinian to resurrect the old empire by reclaiming Italy that nearly doomed the ancient capital he so wanted to rule. Using the assassination of his ally Amalasuintha, Theodoric’s daughter and then Queen of Italy. As a pretext, Justinian sent an army to invade Italy in 535, igniting what historians label as the last of the Gothic Wars.

This was one of those wars that ultimately ends up having no winners at all and becoming a disaster for everybody involved, especially the powerless people whose land was under siege. The Byzantines did eventually retake Italy while the Ostrogoths still managed to rally around a new king a royal on loan from the Visigothic kingdom of Spain named Totila. But nonetheless, catastrophe loomed over them all in the form of the Lombards. The Lombards were another Germanic people migrating south to escape attacks by the Huns and the failed harvests that were a major symptom of the wetter and colder weather caused by sixth century climate change. During the Gothic Wars, they had been a reliable source of mercenaries for Justinian’s invasion force.

But as is often the case today’s tired mercenary is sometimes tomorrow’s enemy. The Lombards turned on the Byzantines and crushed what was left of the Ostragoths, establishing their own Italian kingdom. Although the Byzantines would hold on to the island of Sicily in a good part of southern and northeastern Italy from this point on, Italy would not again be united under one government for another 1300 years. The grueling 20-year war the Byzantines waged against the Ostragoths and the invasion of the Lombards left much of Italy in ruins. The city of Rome, Justinian’s alluring prize, was all but destroyed. Most of the citizens had fled or died from famine caused by the sieges the city suffered. The last working aqueducts were broken and never repaired and the neglected farmland around the city had turned into swamps. Where once there were bustling city streets, there were open fields where the remaining inhabitants let their livestock graze or grew vegetable gardens and fruit trees. It was even said that in a fit of rage Totila considered completely raising even what little was left of the once great metropolis.

In July, a few cities like Concordia and Aqualea, all of which could trace their histories back to the heyday of the Roman Empire and beyond, were completely destroyed by the Lombards. They left behind nothing but a name on a map, if that. It was the refugees from these cities, at least according to legend, who relocated to the lagoons to the south of their former homes and started what would become the city of Venice, which, spoilers will become a major character much later in our story. For now, the Lombards didn’t get to enjoy the spotlight for all that long before they were knocked off the stage by the Carolignians, a dynasty that came to power and what, for the sake of convenience, I’ll call France and founded an empire that stretched from what is now northeastern Spain to Croatia.

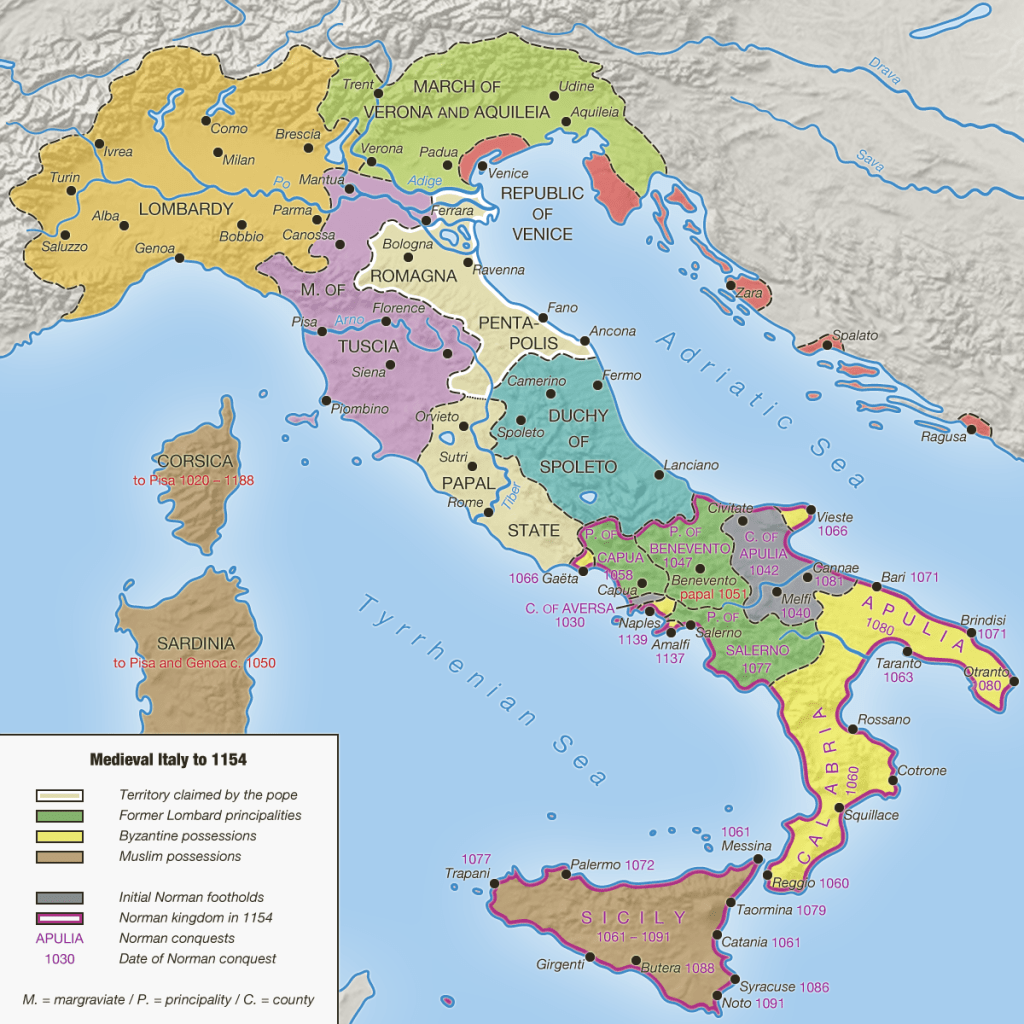

Side note at the risk of complicating and already overloaded narrative, I have to point out, because I know somebody might bring it up the Lombard kingdom did survive in the form of the Duchy of Spoleto and the Principality of Benevento in south central Italy. Carry on.

Under the Carolingians, Italy only fractured even further. The adorably named Carolingian King Peppin granted control of Rome and various lands around central Italy to the papacy in Rome, forming the nucleus of what would become the Papal States. This act would also finally answer the question of what happens when you take the leading figure of a religion whose founder extolled poverty and nonviolence and make him into a territorial magnate with his own feudal army.

The short answer, by the way, is you get centuries of shenanigans. After dividing their empire amongst themselves following the death of Charlemagne, some Carolingians would keep using the old title of King of Italy, even though that kingdom was now mainly just reduced to northern Italy, with some chunks of central Italy, too, at times. After the last Carolingian to rule in Italy, the not so adorably named Charles the Fat was left to rot in prison after coup. The title was fought over by the Carolingians who still held power in Italy, and a series of regional nobles with no less than eight different would be kings of Italy at one point. Now, after rushing through about 200 or so years of history, I want to take a moment to say that if you’re ever abducted by a demented timelord who wants to force you to live in the European Dark Ages, but you at least get to choose which country you have to live in.

You’d probably want to pick Italy. Also, even with this period of invasions, counter invasions, political fracturing, chaos, northern Italy actually did pretty well for itself. Outside the city of Constantinople, northern Italy was the most urbanized part of Europe. Three fifths of the old Roman towns and cities in the region survived, and in fact, archaeological discovery suggests there might have even been some urban growth in this time. This is my own speculation here, but maybe it was because northern Italy remained a gateway for trade between the Mediterranean and Germany and France, where the main political centers of Western Europe had shifted.

Or maybe it was just that northern Italy was part of the old heartland of the Roman Empire, but hadn’t been largely devastated or split apart like central, southern, and northeastern Italy. In any case, the old city-based society of the Roman Empire survived in a way unlike many of the western territories of the former empire, where city life all but evaporated and the most important economic and political centers instead became the great rural estates. In fact, more financial and commercial documents survived from northern Italy than anywhere else in Europe during the Dark Ages, giving an impression of a society that was still fairly sophisticated when it came to commerce and the bureaucratic regulation of it. The following is an actual document from eight-century Milan, translated and edited by Robert S. Lopez in Irving W. Raymond in their primary source collection, Medieval Trade in the Mediterranean World.

It has a bit of a ring of modern bureaucracy to it, although the subject of the document, as you’ll see, will give you a sharp reminder that we’re still talking about a time period very different from our own.

“In the 13th year of the reign of our Lord most excellent man, King Liutprand, on the eight day before the eyes of June 8. Indiction good fortune. I, Faustino notary by royal authority.

Purchase document of sale submitted by Ermadruda, honorable woman, daughter of Lorenzo acting jointly with consent and will by the parent of hers and being the seller she acknowledges that she has received as indeed she at the present time is receiving from Tatone most distinguished man twelve new gold solidi as the full price for a boy of the Gallic people named Fetialano or by whatever other name the boy may be called. And she declared that it had come to her from her father’s patron. And she acting jointly with her efforts that father promises from this day to protect that boy against all men on behalf of the buyer. And if the boy is injured or taken away and they are in any way unable to protect it against all men, they shall return the solidi in the double to the buyer, including all improvements in the object. Done in Milan in the day of the 8th indiction mentioned above the sign of the hand of Ermadruda honorable woman seller, who declared that she sold the aforesaid Frankish boy of her own goodwill, with the consent of her parents and she asked the sale be made the sign of the hand of Lorenzo, honorable man, her father consenting to the sale. The sign of the hand of Theoberto, honorable man, maker of curesus, son of the late Giobanache, relative of the same seller, in whose presence she proclaimed that she was under no constraint giving consent. Honorable witness Antonino, devout man, invited by Ermedruda honorable woman and by her father, giving his consent, undersigned as a witness to this record of sale. I, the above writer of this record of sale after delivery, gave this record.”

Now, imagine trying to rule as a feudal monarch over a society where the warrior nobles out in the countryside, where it’s supposed to help prop you up, don’t actually have that much money and power, but cities do.What this means is, if you want or need a little war, you can’t just pop over to your top magnates territory and ask him and his followers to come fight for you, because they swore guilty. And, oh, yeah, there will be plenty of glory and loot to be had, too. Now, instead, you had to go to these cities, hat or crown in hand, and haggle wwiith the leading citizens for cash and soldiers. And the cities weren’t just going to handle that over.

No, for just one example, king Berengard I of Italy had to go begging the cities to help fund the defense of his kingdom from the raids of the Magyars, better known to you if you’re in the English speaking world as the Hungarians. In exchange, Berengar had to give up special rights, privileges and lands to the cities or their individual leaders. And the really annoying thing about rights, privileges and lands is they’re much harder to take back than to give away. The cycle of needing to chip away at your own power base is king in order to get the support you need to go to war would not end with him either. So that’s the more wider view historian explanation for why we don’t have a unified, independent kingdom of Italy for that long, relatively speaking.

But a more dramatic explanation boils down to the young Pope, not the one played by Jude Law, but the real young Pope. Or, to go by his papal title, pope John the Twelve. He was the illegitimate only son of the nobleman Albaric of Spaletto, at the time the de facto ruler of Rome, who had handpicked the last five Popes. When he realized that he was about to be killed by the fever he was suffering, he gathered together the top citizens of Rome and made them swear over the tomb of St. Peter that they would elect his son, who had just been ordained into the clergy, as next Pope.

They readily agreed the fact that Octavian was only 18 at the time was incident. Their motives are unclear. But they did elect Octavian and made him Pope in 955. There just aren’t that many sources about this Pope, and the only chronicler of his pontificate was Bishop Luitprand of Cremona, who absolutely loathed the kid. In fact, Lupren alleges the following about the young Pope gambled using the Church’s money and maybe even worse when invoked the aid of Venus and Jupiter while rolling the dice.

Women on pilgrimage were afraid to visit St. Peter’s because they had reason to believe they would be sexually assaulted by the Pope. He made his mistress Anna the governor of one of the cities in the Papal States, castrated and killed a subdeacon, slept with his niece and his late father’s former concubine, had his political enemies tongues torn out and their fingers and noses cut off, ordained unqualified men as bishops in exchange for bribes, and never made the sign of the cross. As you might expect, even though he was the contemporary of Pope John’s. Look friend’s account should be taken with a grain of salt, especially given his obvious political bias against Pope John the Twelve.

That said, it’s hard to imagine a teenager who got made Pope for cynical, political and dynastic reasons, waiting to have at least a few peccadillos, even if he wasn’t actually a horrific rapist. At the very least, it can be said with certainty that Pope John was guilty of having some really terrible political instincts. Berengard II, the latest man to claim the title of King of Italy, as well as being now practically empty title of Emperor, was invading territory belonging to the Papal States, so the Pope sent a plea for help to Germany. Now, since the line of the Carolingian family ruling Germany had died out, the most powerful magnates of Germany started electing the next King of Germany from among their own number. The second king they chose was Heinrich the Fowler, the Duke of Saxony.

After his death in 936, his son managed to get elected to secede him as King Otto. Otto had clashed with Berengard a second before, so he must have seemed like a good choice to be the papacy’s protector, at least forward a time. Indeed, Otto would beat Barangar again and had him imprisoned in a Bavarian castle where he would die in captivity. In exchange, on February 962, the Pope crowned Otto and his wife, Adelaide of Burgundy as emperor and empress. By the way, many historians would call this the moment the Holy Roman Empire was founded, even though the actual term wasn’t used until the 13th century.

That’s the kind of compromise with semantics you have to make when you do history. And anyway, I really like having the Holy Roman Empire inaugurated by a top contender for the title of unholiest Pope in history. It’s things like that that make me love the subject. Anyway, as soon as Otto was making his way back across the Alps, Pope John two-timed Otto and offered the crown of Italy and the title of Emperor instead to Berengar’s son Adelbert. Liutprand of Cremona tries to make it sound like Pope John was acting out of pure malice, but it does seem logical he would get buyer’s remorse.

Maybe he learned something that convinced him that Otto was as much a threat to the Papal States as Berengar ever was. Or he realized that with

Berengar gone, he was seriously lacking in leverage against the new

emperor. Whatever his reasoning, though, Pope John badly miscalculated. Otto turned around with his army back to Rome and put the Pope on trial before a papal synod whose participants included our not so trusty narrator. Pope John refused to dignify the trowel of his presence, but Otto and the

bishops pressed on with the charges of sexual deviance, blasphemy, and

corruption. According to Liutprand, Otto even wrote to the Pope, begginghim to appear.

His only response was the letter addressed to the synod itself declaring,

“Bishop John to all the bishops, we hear that you wish to make another

Pope. If you do, I excommunicate you by Almighty God, and you have no power to ordain no one or celebrate Mass.”

Allegedly, the synad’s reply was, “We always thought, or rather believe, that two negatives made an affirmative if your authority did not weaken that of the ancient authors.” Anyway, the Synod, under pressure from the

Emperor, made the superintendent of Rome’s scribal schools Pope Leo

VIII. Despite the problems with John XII, the new pope, Leo VIII, was a

layperson who had to be fast tracked to the ranks of the Church before he could be invested with papal authority.

Meanwhile, in probably the biggest indication that Liutprand’s biography of the young pope is perhaps a tad skewed. Local resistance rallied around Pope John XII, and against Leo. Otto couldn’t even press the point and protect his own nominee. His troops were restless, and it was politically dangerous for him to stay away from Germany for too long. Still, though, Pope John may have escaped both holy and imperial justice, but he could not escape Liutprand’s acid pen. Certainly he didn’t come to a good end either, if you can believe Liutprand at all.

Supposedly, he died at the age of 27, either because he had a stroke while

having sex with a married woman or because her husband caught him and beat him to death. What we can say without any doubt about Pope John is that he signed the death warrants of the kingdom of Italy when he crowned Otto king and emperor. From that point on, the title of King of Italy became inexorably linked with the Holy Roman emperors until, in theearly 16th century, emperor Ferdinand I stopped officially using it. The oldtitle of King of Italy wouldn’t even see the light of day again until the meteoric rise of a French general named Napoleon Bonaparte.

]But now we’re really jumping ahead of where we’re supposed to go. The

point is, the royal title and a dollar would just get you a Coke if you don’t

actually have the territorial control to back it up. Otto already got a taste of his lesson when he found he couldn’t risk an extended Italian workation

to force the pope back in line. His successors would also learn that it’s hardto keep steady control over an entire region when every time there’s a

serious problem, you have to cross the Alps with an entire army and trust

you won’t have invaders attacking or treacherous nobles and bishops undermining your regime back north.

Thanks for listening and buona note.