Transcript

Something about history that usually remains true is that very few people are ever aware of the significance of the times they live through. The Romans of their late fourth century CE didn’t know their children and grandchildren would be the last citizens of the empire nor did the Prophet Muhammad’s contemporaries realize their compatriots would crush the superpowers of their day, the Eastern Roman and Sassanid Empires, and start a religion that would change the world. And no one ever thought of themselves as living through the colonial era or the Enlightenment or whathaveyou. If any generations ever knew exactly what era they were living through, it was the people who lived to see the Renaissance. While it was a nineteenth century historian, Jules Michelet, who did first slap the label “Renaissance” on the whole period, it really was Giorgio Vasari, the humanist who wrote Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects, who coined the metaphor of “rebirth” when referring to the accomplishments of the artists he described in his work.

More importantly, J.R. Hale argues that, while there are always people who think they live in a golden age or a time of decadence, the Renaissance just had a surplus of people who thought they lived in exceptional times that had the potential to be even greater than the golden ages of Athens or Rome. To quote from some of Hale’s examples, a Florentine merchant Giovanni Rucellai remarked in 1457: “Our times since 1400 have greater reason to be contented than any other since Florence was founded.” But this feeling was not restricted to Florence or even Italy. Erasmus exclaimed, “As if on a given signal, splendid talents are stirring.” In 1518, Ulrich von Hutten, poet laureate of the Holy Roman Empire and an early convert to Protestantism, declared, “Oh age! Oh letters! It is a joy to be alive! Woe to you, barbarians!” The Spanish humanist Juan Luis Vives in 1531 wrote, “If only we apply our minds sufficiently, we can judge better over the whole round of life and nature than could Plato, Aristotle or any of the ancients.” And no one less than Martin Luther said, “In this age everything begins to be restored.”

Where did this confidence come from? There are a dozen different directions from which I can approach this topic, but I do think it’s worth considering there was a big change in direction for mainstream intellectual culture. I mentioned before that by the thirteenth century western European philosophy was dominated by Thomas Aquinas and the ghost of Aristotle. To again simplify a really complicated topic, basically the top trend in European philosophy was the view that God organized the universe into universal categories that can be perceived through Aristotlean reason. Like I mentioned in episode seven Apocalypse, the certainty that the universe was a tidy, logical system was shaken to its core by the horrors of the Black Death. An English friar named William of Ockham of Ockham’s Razor fame made one serious objection to this line of thought: if God is truly all-powerful, then why would he be constrained by any categories and universal essences, no matter how logical and neat they are, especially if God could change or suspend them at any time? Ockham’s viewpoint has a name, nominalism, which basically means the argument that categories and essences are just ideas and concepts that exist in the individual’s mind, based on similarities and differences they perceive. To put it recent terms, astronomers struck a huge blow for nominalism when they declared that Plato wasn’t a planet, but a dwarf planet. It was a philosophical stance that had been around before even Christianity, but William of Ockham managed to make it popular. And it probably helped that Ockham’s views came to make more sense in a world turned upside down by the Black Death. Another movement was that western European philosophy up to the thirteenth century tended to view the soul and the mind as the same thing. However, as Islamic philosophy became widely studied and spread in Europe’s new universities, theologians started to agree with Islam that the mind and the soul are distinct. I’m really punching above my weight class by talking about medieval metaphysics, but philosophers like Duns Scotus from, of course, Scotland, but I’ll just skip to the plot twist and say that Scotus’ arguments concluded that the mind and the soul are united in a human being but are still distinct things, and that there is an immaterial realm of the spirit that exists as matter but without a definite form. This put down a groundwork for that separation of the spiritual and the material I mentioned last time.

But wait, you’re probably asking, what does categories and essences and souls being matter without form have to do with the Renaissance? Well, the thing about the nominalism proposed by Ockham is that it really empowers the individual’s view and their own interpretations of the facts. This is in contrast to the usual Scholastic approach, which is to rely on commentaries and interpretations. Instead nominalism, intentionally or not, encouraged people to develop their own ideas based on observation of the original source. And it was that idea that the secular and the religious are two completely separate spheres that would shape politics in not just the Renaissance, but all through the modern age.

But I know you’re here for me to talk about the art and architecture, not what a bunch of theologians bickered about, right? Well, of course the Black Death lurks in the background here too, since art patrons after the Black Death hungered for more detailed and personal depictions rather than the more figurative art styles that prevailed before. And artists just happened to appear who ran with that trend and took it even further. Now like a lot of historians I feel like I have to say I’m not in favor of the Big Man and Woman Theory, that exceptional individuals change history alone, although I will quickly add that I think some modern historians and commentators are guilty of going to the opposite extreme. Anyway, I just want to say that while there is an explanation in the direction culture was going in the decades following the Black Death and with all the money being spent on art patronage, the number of artists with innovations who appeared in so short a time is pretty remarkable and beyond the ability of anyone to just explain away, even historians.

One such artist and arguably the earliest was Giotto di Bondone, although he preferred to go by just Giotto. In The Decameron, Boccaccio declared that there was nothing Giotto could not “could not depict with his stylus, pen or brush so close to the original that it had the appearance, not of a reproduction, but of the thing itself, often causing people’s eyes to be deceived and to mistake the picture for the real thing.” According to the not terribly reliable Vasari, Giotto was born in 1277. He was the son of a peasant farmer in the Mugello, the valley that was also the homeplace of the Medici. As shown in his famous paintings Crucifix and Isaac Blesses Jacob, Giotto gave more detail to the human body, to facial expressions, and to the signs of daily life, like clothing and furniture. He also developed a technique that gave realistic distance between people and objects. Although Giotto came along a bit too early to usually be classified as a Renaissance artist, he still represented the kind of details artists of the Renaissance would focus on.

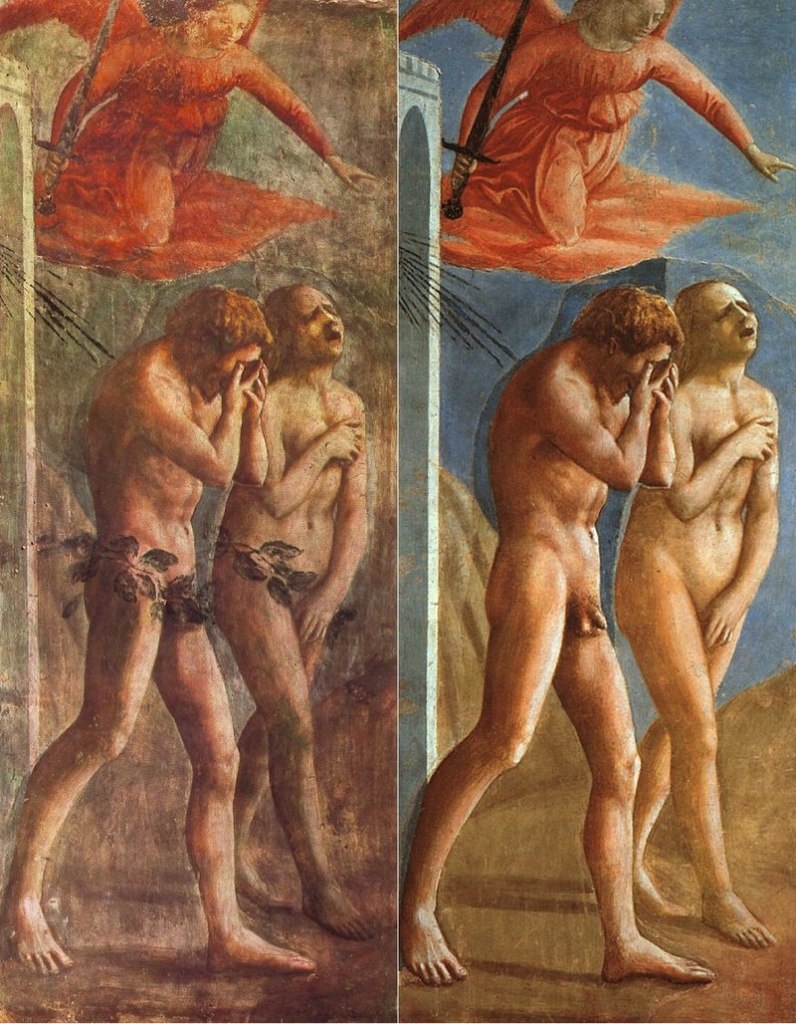

Just as influential if not more so is another artist who went by one name like Prince or Cher, Masaccio. His name came from “Maso”, short for Tommaso or Thomas so you could translate his name into English as “Messy” or “Dirty Tom”. Born in Florence on December of 1401 from a middle-class family, Masaccio embraced art and took Giotto as a model. Even though he passed away suddenly at only the age of 26, Masaccio made so much of a mark that he is regarded as one of the first, if not the first, great artist of the Italian Renaissance. And it is fair to say that Masaccio did his own one-man revolution by extensively using linear perspective in painting based on the perspective of the viewer. Like Giotto, he broke away from the use of colorful ornamentation, which was standard in the Byzantine-influenced art of the High Middle Ages, and emphasized realistic scenes in his art, even though like most Early Renaissance painters his subjects remained scenes from the Bible.

Sculpture also changed, inspired by statues from antiquity. Breaking with centuries of Christian prudishness over nudity, Donatello’s bronze statue of King David shows the biblical hero nude except for shoes and a hat. It is the first freestanding statue depicting a nude body since antiquity. The statue is something of an art history mystery. There’s no indication that the statue being the first nude to be carved in over a thousand years inspired a single angry yelp from the public. It’s not even known when Donatello made it or for whom; just that he probably carved it sometime in or around the 1440s. What we can say is that it had to have been something of a bombshell, despite the silence in the historical records. After all, not only was Donatello bringing back the ancient pagan Greek fad for nude statues, but he was applying it to a celebrated biblical hero. Still, though, maybe there wasn’t that much controversy after all since Donatello’s statue was put in the town hall of Florence. Despite the occasional outburst of disapproval, nude sculptures became famous, at least within the confines of depicting figures from the distant past. The art historian Kenneth Clark had this to say in The Nude: A Study of Ideal Art: “The nude had flourished most exuberantly during the first hundred years of the classical Renaissance, when the new appetite for antique imagery overlapped with the medieval habits of symbolism and personification. It seemed then that there was no concept, however sublime, which could not be expressed by the naked body, and no object of use, however trivial, which would not be the better for having been given human shape.”

There were limits to what you could do with the nude, though, but we’ll get to that. For now, though, let’s talk about the other great visual art of the time, architecture. But one historian of architecture Christy Anderson argues Renaissance architecture didn’t start in Italy. To celebrate a victory over Castile, in 1386 King Joao I (Joe-ow) of Portugal commissioned a great cathedral, the Monastery of Batalha. It was first designed by the architects Alfonso Domingues and later Huguet. Instead of just being built using traditional Gothic style, it also incorporated elements of Arabesque and local Portuguese design. It was a living transition away from an international Gothic style to national styles of architecture, which would also adapt Renaissance notions of order and symmetry.

If this new style was devised by anybody, it was Filippo Bruneleschi. The son of a well-off lawyer, he was born in Florence in 1377. Not only was he an architect and engineer, but a painter and sculptor who arguably did as much as Masaccio to perfect and spread the idea of linear perspective in painting.

Even though he came from a rich background, Brunelleschi embraced the image of the eccentric artist. To go by the description in Ross King’s Brunelleschi’s Dome: How a Renaissance Genius Reinvented Architecture: “…Filippo was short, bald, and pugnacious looking, with an aquiline nose, thin lips, and a weak chin. His appearance was not helped by his dirty and dishelved clothing. Yet in Florence such an unsightly display was almost a badge of genius, and Filippo was the latest in a long and illustrious line of ugly or unkempt artists.” Brunelleschi worked on a number of prestigious products, including on the Medici’s own Basilica of San Lorenzo, but his biggest win was the dome of Santa Maria del Fiore Cathedral. Started in 1296, the cathedral was still without a dome since no one could figure out how to put it on, making the cathedral something of a national embarrassment. In 1418, the government of Florence announced a competition, seeking an architect who would finally solve the problem of the cathedral’s dome. To his contemporaries, Brunelleschi’s idea for fixing this century-old problem was audacious. He proposed to build it without wooden centering, which every dome had. When the city wardens demanded that he share the technical details of his plans, he refused. At one point, the wardens called him “an ass and a babbler” and then physically tossed him out of where they were meeting. We still don’t know how Bruneleschi won them over. According to legend, Brunleschi challenged the wardens by telling them the commission should go to whoever can make an egg stand on end on a flat piece of marble. The others failed, but Filippo simply cracked the egg on the bottom and stood it upright. When his rivals protest that they could have done the same, Filippo retorted that they would have known how to raise the dome too. In any case, Brunelleschi was right. Using physics, he found a way to make the dome stand on its own, without the need for any buttresses.

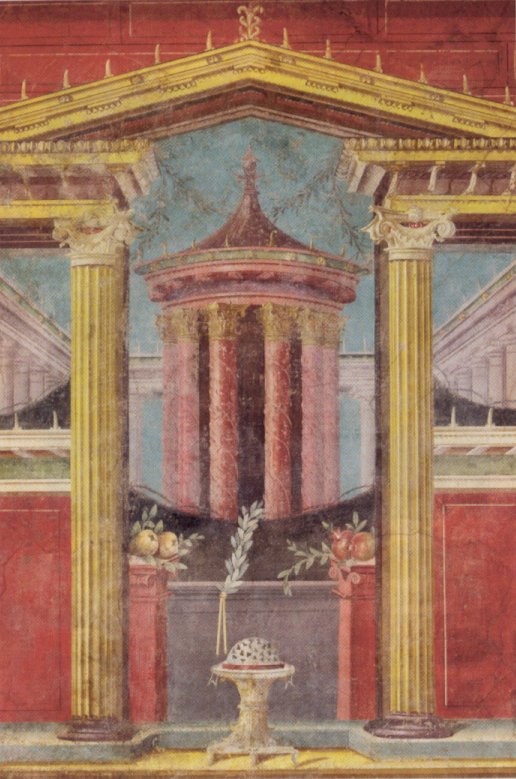

Beyond his engineering feats, Brunelleschi also set the tone for Renaissance architecture. Not unlike the painting of his contemporaries, he tossed away the ornamentation of Gothic architecture and instead preferred a simple balanced, geometric look that both invoked the classical past and represented something new. As Chrissy Anderson describes his style, “The Renaissance, as well as the modern, viewer of Brunelleschi’s buildings is invited to believe that there is an underlying order and system to the building, an almost innate order that regulates each aspect of the building. Perhaps this is a divine presence, mediated through the hand of the architect, but Brunelleschi’s architecture evokes a rational calm that shapes the interior space.”

Music changed around the same era, too, just not in Italy. Innovations in music also happened, just in what is now the modern-day Netherlands, what was then the northern duchy of Burgundy, rather than in Italy. But it probably wasn’t a coincidence this also happened in a region of Europe whose wealth and cosmopolitanism rivaled that of northern Italy. However, many of the most prominent musicians did eventually make their way to Italy to receive patronage. For example, there was the Flemish composer Josquin des Prez, famous in his own day, who innovated how melodies could carry the meaning of words. Here’s a performance of El Grillo, “The Cricket”, one of his secular songs. By the start of the sixteenth century, monarchs and nobles began for the first time to rival the Catholic Church in sponsorship of music. Also, according to Howard M. Brown and Louise K. Stein’s Music in the Renaissance, music also began to reflect humanist ideal of elegant rhetoric. I’m going to level with you. I’m tone deaf and not at all familiar with any of the technical aspects of music composition. But it sounds important and interesting so I thought I’d include it anyway.

As I mentioned, these painters, musicians, sculptors, and scholars were all receiving patronage across Europe, and not just from the big royal courts or people like the Medici. There was even competition to offer patronage to the latest hot sculptor or poet. See, in ancient and medieval times, painters, sculptors, architects, and other people who worked in what we might call the visual arts we thought largely in the same terms as carpenters or dressmakers. The idea of celebrity artists, which was extremely rare if not unheard of in earlier centuries, suddenly became commonplace. A Dutch artist like Jan van Eyck found himself famous not only in his native Netherlands, but could get sponsorship offers from the kings of Portugal and Spain too.

Plus It’s important to note that patronage was also handed out by not just royals and famous families like the Medici, but lesser-known patrician families. For example, there’s the Strozzis, the second wealthiest family in Florence by Cosimo de’ Medici’s time, which, yes, makes the Strozzis the Flintheart Glomgold to the Medici’s Scrooge McDuck. Also, they didn’t just pay artists and scholars, but were sincere in their devotion to the arts and knowledge as well. The family patriarch, Flilippo Strozzi, translated selections of the Greek historian Polybius into Italian and wrote his own music compositions.

Women could serve as patrons, although, like I noted last time, they were usually women who had complete control over their own finances, so mainly widows or nuns. One such woman was Isabelle d’Este, wife of the Marquis of Mantua, who collected art works by Bellini, Perugino, Leonardo da Vinci, and Titian. She may even actually be da Vinci’s mysterious Mona Lisa.

But what about women who participated in the Renaissance themselves? There was a renowned female humanist who was born in 1418 in Verona, Isotta Nogarola. Following the lead of her aunt Angela Nogarola who was a poet, Isotta wrote a biography of St. Jerome and a Latin treatise, titled “Dialogue on the Equal or Unequal Sin of Adam and Eve.” It argued that the prevalent idea that Eve was more responsible for causing original sin was absurd, if it was also true that women were the weaker sex. Finding nothing but hostility and sexism from her enemies and condescension from her sympathizers, Isotta retired from public life. To her former tutor, a celebrated scholar named Guarino da Verona, she wrote, “You yourself said there was no goal I could not achieve. But now that nothing has turned out as it should have, my joy has given way to sorrow… For they jeer at me throughout the city, the women mock me. I cannot find a quiet stable to hide, and the donkeys tear me with their teeth, the oxen stab me with their horns.”

Perhaps somewhat happier was Lavinia Fontana from Bologna, the earliest known professional female artist, whose father Prospero may have encouraged her to become an artist because he had no son to follow his career. She catered especially to an audience of female patrons, who would have been much more comfortable employing another woman than male patrons. Her art depicted herself as a modest and respectable woman. She sent one such painting, “Self-Portrait with a Maidservant”, to her future in-laws, an impoverished but noble family, in order to help convince them to let her marry their son. To quote the art historian Geraldine Johnson, “The painting was executed by Lavinia and sent to her future-in-laws in order to assure them of her social graces, pleasing appearance, and many accomplishments, all necessary attributes for a bride intended for a gentleman of good breeding. Furthermore, the self-portrait could have helped to convince her future husband that she fully intended to uphold her side of the marriage contract, which entailed her contributing to the family’s economic well-being through her art. Significantly, Fontana’s self-portrait includes an easel and a cassone – the one a tool of her trade, the other a piece of furniture generally associated with marriage and dowries. Without a dowry herself, Fontana was thus demonstrating to her husband and his family by visual means that she possessed a valuable talent that could stand in lieu of – and perhaps could even surpass – a cash dowry.”

In fact, women ran afoul of one of the darker sides of the Renaissance. The rediscovery of Roman law in the twelfth century, which had held that women could not control property without a male guardian, actually helped weaken women’s power. This can be hard to understand for us, since we are all raised with the notion of historical progress. However, the Renaissance actually saw the influence of at least upper-class women declining. This was initially true especially in places in republics like the Italian city-states than in feudal monarchies, where women at least could claim power through their marriages or family relationships. As Joan Kelly noted in her essay “Did Women Have a Renaissance?”, “Their access to power was indirect and provisional, and was expected to be so.” However, the trend spread across Europe. For example, noble women in France could participate in the meetings of regional assemblies called parlements, but, by the seventeenth century, women could only observe the meetings from the sidelines. This is not to say royal and aristocratic women did not receive quality educations. It’s just the point of their education was seen as improving their ability to appeal to their husbands and to raise sons. Maybe the best example of the contradictory attitudes toward women and education came from Juan Luis Vives, who as Queen Mary I’s tutor helped make sure she was one of the best educated women to ever sit on the English throne, also taught Mary that as a woman she was “the Devil’s instrument, not Christ’s.”

As Joan Kelly observes when discussing Baldesar Castiglione’s “The Book of the Courtier” which describes nobles gathering to debate over the ideal courtier, women are excluded from the conversations and just serve as moderators or entertaining the guests with music and dancing. But both elite women and men were expected to follow this culture of etiquette. Of course, etiquette and its importance among the elite is as old as civilization itself, but it had a particular popularity in the Renaissance. If people were not fallen creatures of original sin but exalted beings who were products of both godlike reason and animalistic desires, as the humanists thought, then the best way to show one’s worth, even one’s virtue, was through signs of ability, intelligence, discernment, and sophistication. After all, Castiglione concludes that the ideal courtier was a man of the world, a skilled warrior and an athlete but also a cosmopolitan individual with a well-rounded education. Showing class and taste was a sure sign of one’s inner qualities. The Florentine matriarch Alessandra Strozzi says as much when she describes the eating habits of prolific book hunter Niccolo Niccoli: “When he was at table, he ate from the most beautiful antique dishes and the whole table was covered with porcelain and other very elegant dishes. He drank from crystal and other goblets of precious stone. What a noble sight it was to see him at table, as though he were a figure from the ancient world.”

If the new civility meant people who could show off their bling were good, then you can imagine what they thought of rural peasants. Again, overall this isn’t new, but the prevailing attitudes made it easier to just completely dehumanize not only the poorest of the poor, but peoples who didn’t match European elites’ exact standards for a civilized people, whether they were the Irish in the eyes of the English or Amerindians as seen by the Spanish and Portuguese. As the Spanish lawyer Francisco de Vitoria described Amerindians: “I for the most part attribute their seeming so unintelligent and stupid to a bad and barbarous upbringing, for even among ourselves we find many peasants who differ little from brutes.” Soon enough, the civilizing mission became the quote-unquote humanitarian justification for European colonization.

But these growing standards for human behavior also converged with the confidence that societies may be changed for the better. At the same time, by the end of the fifteenth century Europe was plunging headfirst into another economic and demographic revolution. Competition for even menial jobs grew in the now overcrowded cities, the influx of gold and silver coming in through Portugal and Spain from the American colonies was causing massive inflation, the urban bourgeois were buying up more land and driving more poor farmers off their land, and apprentices were stuck in low-paying jobs with no hope of ever getting promoted to the rank of masters. Under the spiraling income inequality and the population increase, what welfare systems were provided by the Church and city governments were under intense strain.

With this as the backdrop, governments and authorities across Europe cracked down. Now if you follow one of my favorite podcasts, Last Podcast on the Left, you might have heard their own episodes on the Black Death, during which they made the observation that people just seemed more…free during the Middle Ages. Even though by their own admission they’re not historians, they have a point. Guide manuals on etiquette argued increasingly against farting, eating with fingers, and talking in church during the sermons. But there were more ominous and less harmless signs, too. Sodomy laws were more harshly enforced, especially by the Spanish and Portuguese Inquisitions, and some local governments like the Protestant city of Geneva started imposing draconian laws against adultery, promiscuity, obscene songs, and even just badmouthing the clergy. Laws against panhandling spread and the poor were forced into state-run workhouses and reformatories or at the very least made to jump through regular bureaucratic loops and undergo regular state inspections. It’s worth remembering it wasn’t the governments of the allegedly primitive Middle Ages but the rulers of the more civilized post-Renaissance world who made the Inquisition brutally persecute Muslims and Jews in Spain and Portugal and who started the notorious witch trials.

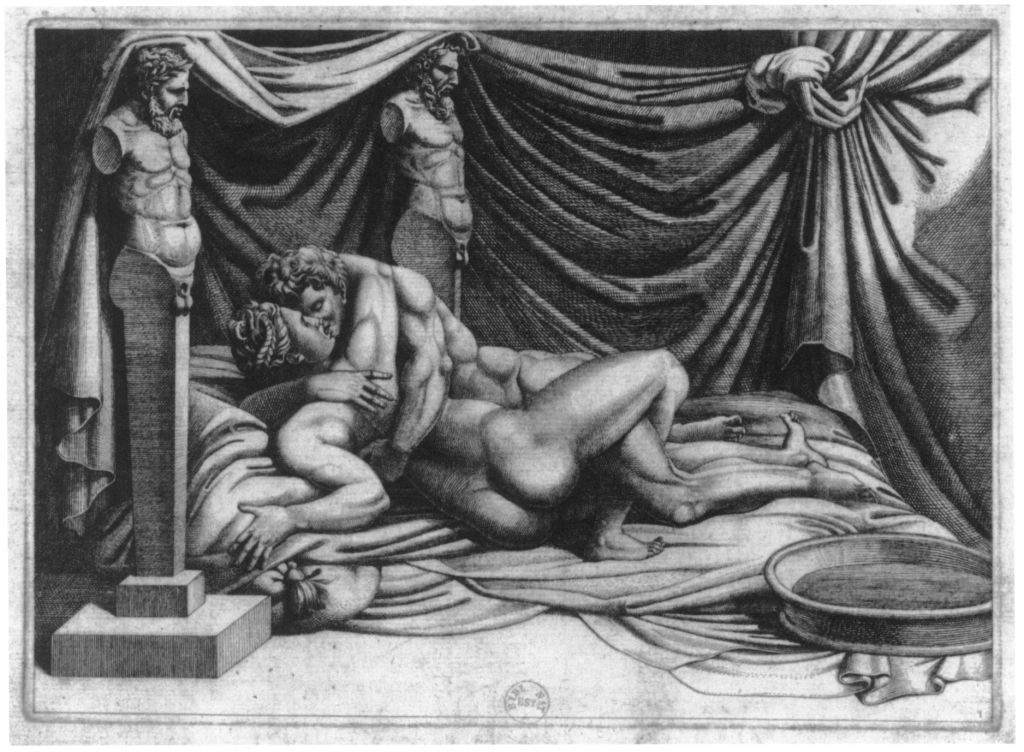

Perhaps the biggest threat faced by these more intrusive governments was made by the printing press. Erotica had always been around, naturally. And if you ever read Chaucer or Boccaccio you would know that dirty, lewd jokes were a proud part of medieval literary culture. However, the unbridled power of the printing press, which could produce enough copies of pamphlets, broadsheets, and books to shockingly reach people outside the elites and even the illiterate, brought about a reaction. The worst was I modi, “The Positions”, the first known work from the Renaissance to show people who weren’t pagan gods or classical figures nude and in erotic poses. The first edition was created by the engraver Marcantonio Raimondi, a former apprentice of Raphael, who based the images off of a series of paintings by Giulio Romano. I modi quickly became a hit, spreading across Europe. Marcantonio was imprisoned and copies of I modi were gathered up and destroyed. This was just the beginning. By the middle of the sixteenth century, the Church and most governments in Europe had elaborate systems for sniffing out forbidden books. The main concern was finding out books with heretical and politically subversive ideas, but they were also worried about lewd books like I modi and their potential to corrupt the unwashed masses. The Council of Trent that took place between 1545 and 1563 went so far as to ban nude images. Thus painters were commissioned to cover up nude figures in paintings with tasteful loincloths while nude statues had their genitals hidden under metal fig leaves. Literature that would be labelled as obscene in later eras was still enjoyed by respectable people throughout the sixteenth century, but on the whole the Renaissance did bestow on the West the idea that culture can be a threat to the state and to society itself.

There really isn’t a tidy way to wrap up this episode, so…I’m not going to try. State-managed cultural censorship, celebrity artists, the decline in women’s political power…these are all legacies of the Renaissance that would define what we still think of as modern world. Besides the fact that it would be just…wrong to do a podcast about the Medici without at least an episode about the Renaissance, I do think it’s important to show the Medici came around in a world that was experiencing pretty core changes in a really short amount of time. Especially because the Medici themselves would build on the foundation the Renaissance gave them and make their own decisive contributions to modern history.

Join us next time as we talk about Cosimo de’ Medici whose political career was almost brought to a disastrous end before it had a chance to really begin.